Intrigued by a painting of the sailing vessel SV Madagascar, which can be viewed at the Shipwreck Centre & Maritime Museum, Isle of Wight, MAT volunteer, Roger Burns, set out to discover its story. Here, Roger explores the history behind the ship, including its connection to the Female Emigration Fund, and a gold-linked mystery disappearance. Discover the mystery of SV Madagascar by reading below.

The Ship

SV Madagascar was a Blackwall Frigate built by Green, Wigram’s and Green at Blackwall. It was launched on 20 May 1837. ‘Blackwall Frigate’ was a colloquial name for a “type of three-masted full rigged ship built between the late 1830s and the mid-1870s” from which the description continues:

“They were originally intended as replacements for the British East Indiaman in the trade between England, the Cape of Good Hope, India and China, but from the 1850s were also employed in the trade between England, Australia and New Zealand……..The Blackwall frigate had a single gallery and was so named partly because it was superficially similar in appearance to a frigate of the Royal Navy. Blackwall frigates were fast sailing ships, although not as fast as the clipper ships that appeared in the late 1840s. Madagascar launched in 1837, was one of the first two Blackwall frigates built……

Over 120 Blackwall frigates were built by British and Indian yards. They were generally considered to be safe and comfortable ships and were employed in premium trades, but were the victims of some of the most celebrated shipwrecks of the 19th century”.

Madagascar was 150ft. 7ins (c.45.9m) with beam 32ft. 7ins (c.9.93m), depth of hold 22ft. 5ins (c. 6.83m) and, when fully laden, had a draught of 15ft. (c.4.6m). Its home port was London and its owners remained the Green family. Madagascar was constructed of wood, in a combination of English and African oak with fastenings of treenails and copper and at some stage acquired yellow sheathing. Originally, it was equipped with one longboat and two other boats.

Initial Trade Route (1837 – 1852)

The Madagascar sailed from Gravesend on 10 July 1837 under Captain W.H. Walker calling at Portsmouth, Calcutta and Bengal. This voyage was repeated, once departing Gravesend on 20 July 1838, calling at Portsmouth and Falmouth and arriving at Bengal on 22 January 1839, and once again in 1840. By 1841, Madagascar’s captain was C.G. Weller. By February 1849, its captain was Captain Hight, who arrived in the London docks from Calcutta via Madras, Cape of Good Hope, and St. Helena.

During this period, Madagascar had undergone routine repairs and Lloyd’s surveys and successfully retained its original Lloyd’s Class 12A1 rating. However, the Lloyd’s Report of 28 February 1853 is additionally entitled Report of Survey for Repairs & restoration for Madagascar, indicating that more extensive work was undertaken. This work was undertaken between 21 January and 28 February 1853 and involved new foredeck timbers and planking, some 400 treenails, and other work that is difficult to interpret from the handwriting of the day. Again, it was signed off with Class 12A1.

A Change in Route

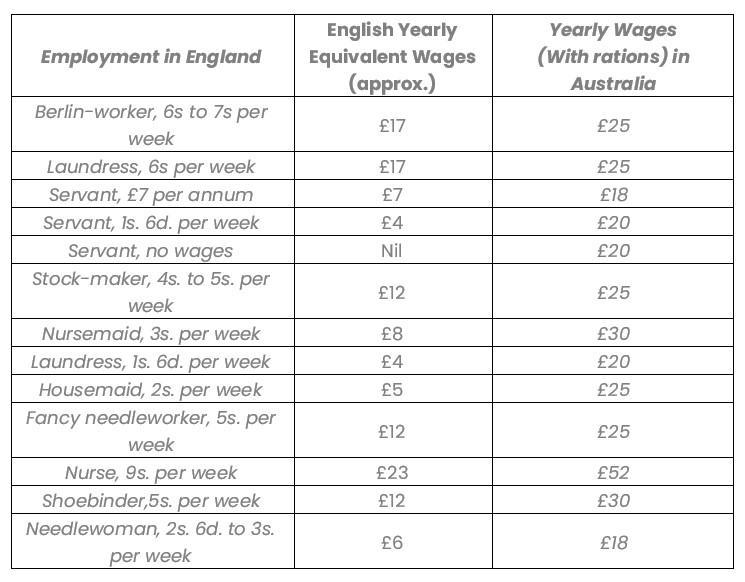

During 1849, there was a growing realisation in Britain that the significant preponderance of numbers of women over men had grown appreciably since the 1820’s and had reached approximately 500,000. This imbalance was partly due to forced and voluntary emigration, especially of men, and the adverse effect on the female working population had become serious. This was demonstrated by the high numbers women employed in occupations such as slopping-out and needlework, which was impacting on wages and a state of borderline poverty.

On 5 December 1849, a long letter written by the Right Hon. Sidney Herbert appeared in the Morning Chronicle and was quickly taken up by other publications. This letter set out the causes and very difficult circumstances of women, noting that their wages were between 4½d. and 2½d. a day (very approximately £500 per annum in 2020 prices). Sidney Herbert proposed a national fund for emigration of ‘ladies of good character’ in significant numbers to the then colonies, mainly to Australia, where there was a significant but opposite imbalance in numbers of men and women. The fund would be open to donations by anyone and would be administered by an appointed committee. The published letter acknowledged that the authorities in the colonies would need to ensure safety of the emigrants and provide assistance in placements. Letters in the media subsequently confirmed that this was indeed actioned. Queen Victoria and Prince Albert donated £500 (approximately £69k in 2020) as reported in the media, including in a letter appearing in April 1850 in the Australian media, which confirmed the involvement of the Australian authorities. It should be noted that other contemporary emigration programmes were unaffected.

Against a background of the Australian Gold Rush, and the Female Emigration Fund, Madagascar had been transferred to the Australian trade and departed Gravesend on 6 March 1853 with female emigres for Port Phillip, a bay that includes Melbourne. From 1852, the captain was Fortescue William Harris, a veteran of voyages to China, the East and West Indies, including the previous trip to Calcutta and back as Madagascar’s commander.

An article appeared in the Illustrated London News of 12 March 1853 describing the Female Emigration Fund. It referred to those emigres who travelled on the Madagascar to Australia in 1853. It mentioned that the Fund had quickly “reached upwards of £22,000” (approx. £3m in 2020) and in the years 1850-1852, over 1,000 women benefitted from the scheme. The newspaper included “The list of occupations from which women were taken in London is in itself remarkable. There were artificial-flower-makers, box-makers, brush-makers, carpet-bag-makers, gelatine-packers, gold-burnishers, lace-transferrers, and furriers; these are, of course, exceptional employments. The vast proportion of the emigrants lived by the dreary labour of the needle”. It continued with the following comparative table of income by profession to which has been added the English annual equivalents, and the data “relates to forty-nine young women, who landed in March 1852 at Port Philip:”

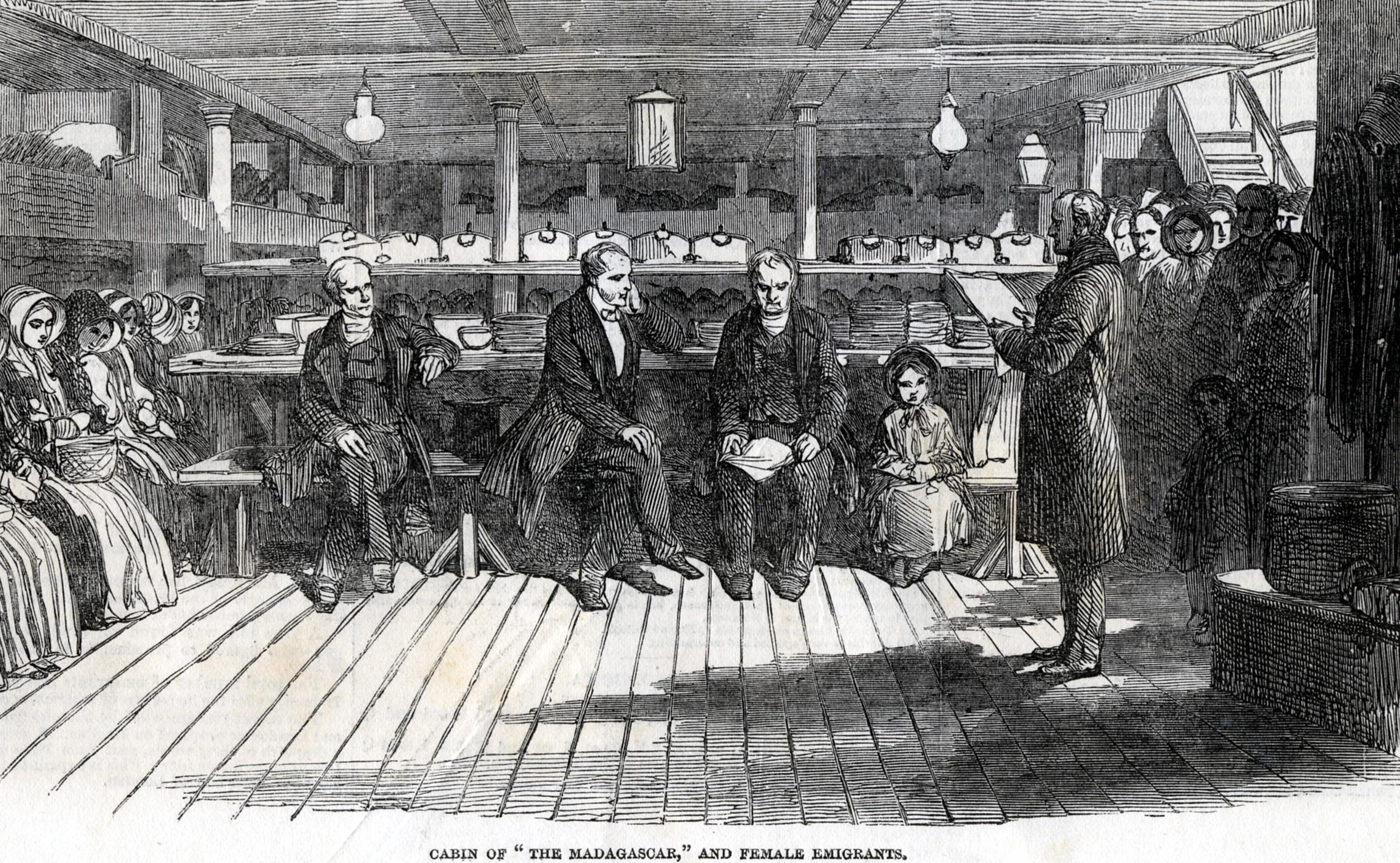

For Madagascar, the article continued: “Forty emigrants, of ages ranging from seventeen to thirty-two, and who had hitherto been seamstresses, stock-makers, shoe-binders, domestic servants etc……….. were accommodated in a most commodious and convenient cabin…..especially fitted up amidships for their accommodation.

The party having arrived at Gravesend, went on board the Madagascar, where the girls were immediately mustered in their cabin, and received each, in rotation, a copy of a letter of directions and advice which had been addressed to them by Mrs. Herbert. (Figure)

Lord Robert Grosvenor then delivered a few parting words to them in the name of the committee, and read to them an excellent letter of advice from Mrs. Herbert. The Rev. Mr. Quickett also addressed a few farewell words to the girls, in the course of which he observed that when the last party reached the colony, no fewer than 300 persons assembled to engage them. They ought to be extremely cautious, and not make any engagement that the Government did not sanction”.

The Fascinating Mystery of SV MADAGASCAR

Madagascar had departed, as mentioned, on 6 March 1853, arriving via Portsmouth at Melbourne on 10 June 1853, whereupon “fourteen of the crew jumped ship for the diggings”, no doubt the allure of gold overriding other considerations. Only about three replacements were signed on for the return voyage. Prior to the return voyage, the Melbourne Argus carried advertisements for its voyage to London. The advertisements were for spare places – £84 for Cabin passengers and £47 for Second Cabin – and passengers were assured of a liberal table throughout the voyage and an experienced surgeon aboard. The advertisements also referred to the repairs and restoration carried out in London earlier in 1853, extolling the fact that it was rated A1, although also necessary for insurance purposes.

For the return voyage, Victorian Heritage Database records that:

“The Madagascar rode at anchor with a full passenger list and large cargo of gold for about a month. Detectives boarded the ship before it departed and arrested several passengers believed involved with the McIvor Gold Escort Robbery near Kyneton in July 1853. The Madagascar departed Melbourne in September and was never seen again. Theories as to the ship’s final resting place range from the Pacific Islands to the coast of Chile or Brazil in South America. Another theory is that the ship and its precious cargo of gold was seized by pirates and all the passengers killed”.

This is further confirmed in a blog together with a photograph of Captain Harris, from which the below excerpts are quoted:

“The disappearance of the Madagascar was one of the great maritime mysteries of the 19th century and was probably the subject of more speculation than any other 19th century disappearance except for the Mary Celeste. She then loaded a cargo that included wool, rice and about two tonnes of gold valued at £240,000, and took on board about 110 passengers for London. ….The Madagascar did not leave Melbourne until Friday 12 August 1853 and after leaving Port Phillip Heads she was never seen again. When the ship became overdue many theories were floated, including spontaneous combustion of the wool cargo, hitting an iceberg and, most controversially, being seized by criminal elements of the passengers and/or crew and scuttled after the gold was stolen and the remaining passengers and crew were murdered”. (£240,000 in 1853 is approx. £31m in 2020)

An internet article gives unsubstantiated speculation that a wreck found on the atoll Anuanuraro in 1997 was believed to be the wreck of the Madagascar along with some artefacts. Anuanuraro is approximately midway between Australia and South America in the south Pacific, which would indicate that the return route was via Cape Horn, thus taking advantage of prevailing westerlies for much of the voyage.

Another article, which is too long to fully copy here, can be found under the title: Two Tons of Gold: The Fate of the Madagascar – Has she been found? The opening paragraphs are pertinent:

“This ship has fascinated treasure hunters for 160 years, because her wreck has supposedly never been found. What makes her interesting to most people is her cargo, 60,542 ounces of gold dust, more than two tons, packed into 86 boxes, and nine crates of gold sovereigns, containing many thousands of these valuable coins. At today’s prices, that gold would be worth over US $100,000,000. The frigate-built Blackwall Liner was last seen sailing out of Hobson’s Bay, at that time the name of the port of Melbourne, Australia, in August, 1853. She was bound for London and her normal route would have taken her there via Cape Horn, but did she really sail in that direction?”

The article continues with the above mentioned arrest and speculation of possible areas where the wreck might be.

The London Daily News of 29 October 1853 listed nine ships known at that time to be carrying gold from Sydney, Geelong and Port Phillip for England, totalling 151,317 ounces, of which Madagascar’s share was 6,460 ounces.

The exact numbers of those who presumably perished is unknown but approximates to 60 crew and 110 passengers. The differing weight of gold carried varies according to source.

We hope you enjoyed reading about the mystery of SV Madagascar. Please explore our blogs for more maritime archaeology and naval history:

- Maritime Archaeology Trust: https://maritimearchaeologytrust.org/blog/

- Shipwreck Centre & Maritime Museum: https://museum.maritimearchaeologytrust.org/blog/

Excellent! We are investigating the fate of Blackwall Madagascar. We are following leads that may soon unravel this mystery. We need all the information we can get so that we can confirm that the shipwreck we found in the northeast of Brazil is from Madagascar. Please send us all the information about this vessel.