Knowing the depth of water under a vessel near land, reefs and harbours has always been vital to mariners for avoiding going aground. While modern nautical charts and instrumentation make this task relatively easy, have you ever wondered how mariners of yesteryear determined depth? A lead weight springs to mind but there is more to this than you might think. Volunteer Roger Burns takes a look at the history of how this essential task developed into the 21st century.

Some Terminology

Sounding – derived from the old English Sund meaning sea.

Fathom – standard measurement of depth or the length of ropes and cables and depth of water. Derived from the old English word for an embrace, fæðm, it was the distance between the outstretched arms of a man and became standardised as six feet. A fathom is 1.8288 metres exactly. The British Admiralty defined a fathom as one thousandth of an imperial nautical mile. (Modern charts use metres).

Plummet Line – device used by the sailor to test the depth of the water. It consisted of a weight (often lead) attached to a thin marked rope. Akin to a plum bob which has a point for establishing a vertical axis.

The Beginning

As far back as 1,800 B.C., the Egyptians are credited with using poles which obviously had limitations beyond say 30 ft / 10m depths to the seabed, similar to the ones illustrated in Figure 1 from an Egyptian tomb painting from 1,450 BCE.

Figure 1: “Officer with sounding pole….is telling the crew to come ahead slow. Engineers with cat-o’-nine tails assuring proper response from the engines”

Source: National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Central Library.

The original uploader was Jonathunder at English Wikipedia, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

John Peter Oleson’s excellent paper “Testing the Waters: The Role of Sounding Weights in Ancient Mediterranean Navigation” opens with “The account of St. Paul’s stormy voyage and shipwreck in the autumn of A.D. 60 is one of the most vivid and convincing narrative accounts of a ship’s last moments to have survived in Greek or Latin literature (Acts 27:13–20, 27–32). As a result, it is frequently cited in publications concerned with Roman navigation”. Continuing, it refers to “casting sounding weight” thus demonstrating the use of a sounding device some 2,000 years ago.

Sounding Devices

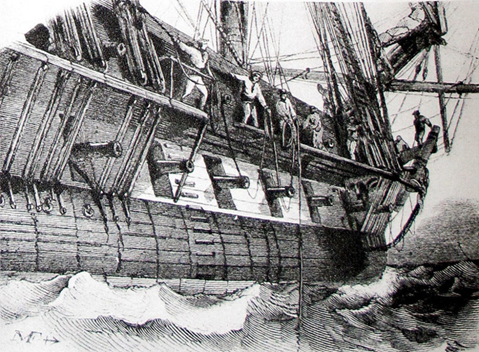

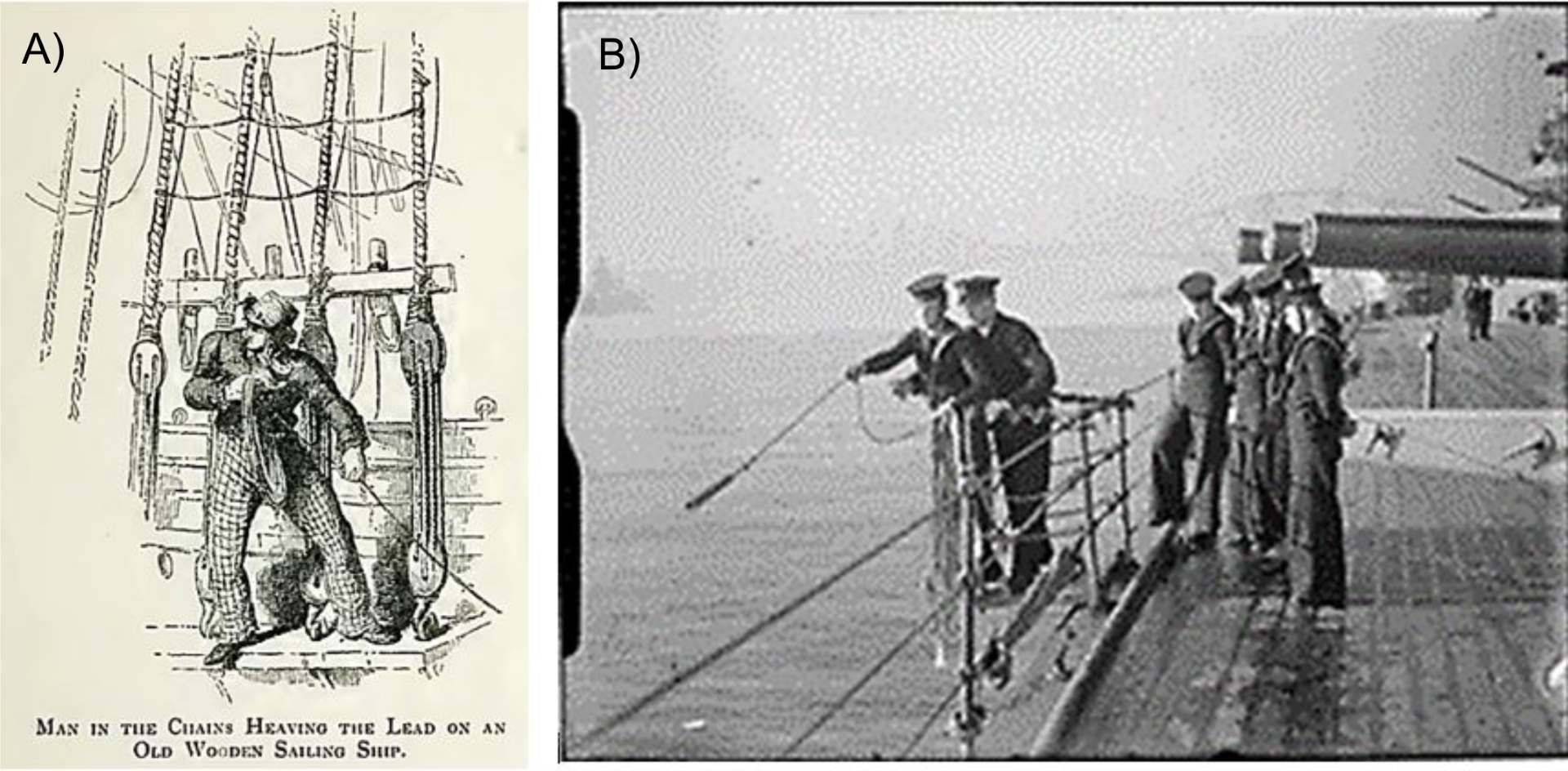

At its simplest, a sounding line or lead line comprises thin rope with attached markers suspending a weight, often of lead and still called “a lead” when other materials are used. The attached markers, tied at every two or three fathoms such as 2, 3, 5, 7, 10, 13, 15 17, 20, are used to establish the depth of the lead below the water. The markers were made of leather, calico, serge and other materials, often with different textures, and usually tied in various shapes, so they could be readily distinguished even at night. A leadsman would call out the depth according to the appropriate mark; if water level was at a mark, he would call, for example, “by the mark 7” which would mean 7 fathoms (or 42 ft or 12.8m) and if between marks, he would call out, if say half way between the 3 and the next marker, “a half 3” and so on. The “leadsman” would usually stand in the “chains”, a small platform projecting from the side of the ship such as in the three examples, Figure 2 & Figures 3A &3B below.

Figure 2: Antoine Léon Morel-Fatio, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Figure 3A: Illustrator unknown, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Figure 3B: WW2. On board HMS RODNEY “Boys” receiving instruction on how to “heave the lead”. The lead weighs 10 to 14 pounds and the picture shows a Boy standing in the “chains” about to heave the lead.

Going in and out of harbour a Leadman is always in the chains taking soundings which he calls out to the bridge.

The Forth railway bridge can be seen in the distance.

Coote, R G G (Lt), Royal Navy official photographer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Mechanical Devices

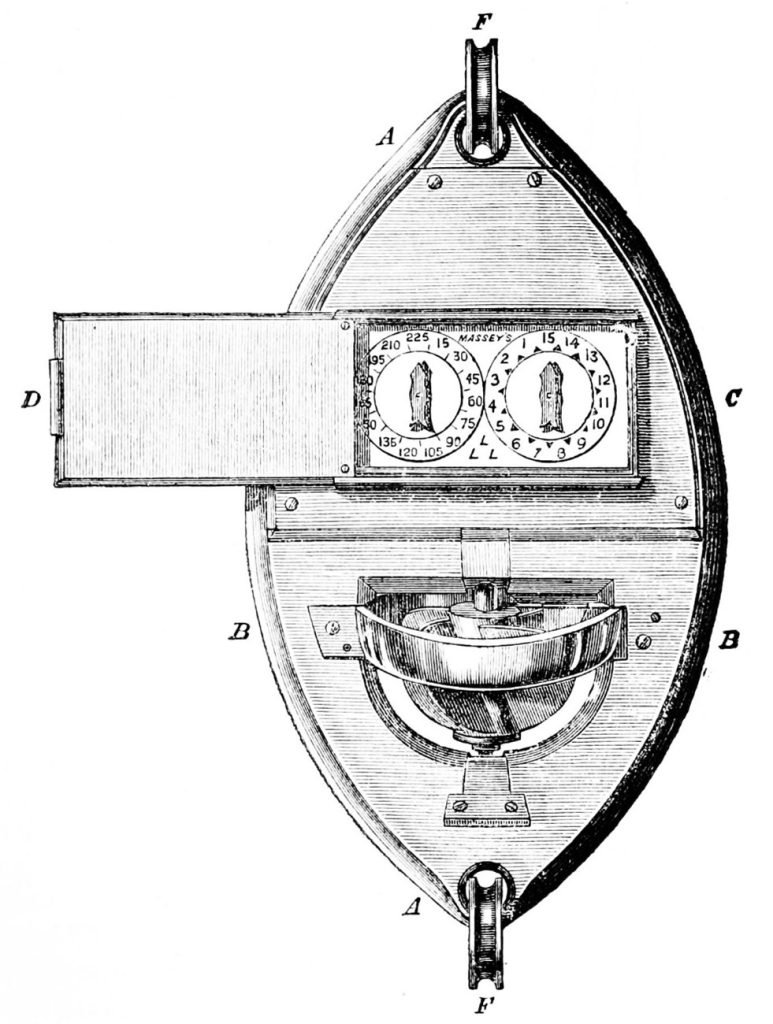

The 18th century saw the introduction of mechanical devices, three of which are described below. In 1802, a clock maker, Edward Massey, invented a machine which proved to be very popular, and by 1811, every Royal Navy ship had one. Illustrated in Figure 4, a traditional sounding lead line was connected to it and while the weight was sinking towards to the seabed, a small rotor was turning a dial. Reaching the seabed, the mechanism would lock, thus ceasing to count the fathoms of depth, and when hauled aboard, a more precise depth could be read. A Royal Museums Greenwich post gives further insight to the introduction of this device.

Figure 4: Edward Massey Sounding Machine

Popular Science Monthly Volume 3, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia gives via CC BY-SA 4.0: The Board of Longitude was instrumental in convincing the Royal Navy to adopt Massey’s machine. Massey’s was not the only sounding machine adopted during the nineteenth century. The Royal Navy also purchased a number of Peter Burt’s buoy and nipper device. This machine was quite different from Massey’s. It consisted of an inflatable canvas bag (the buoy) and a spring-loaded wooden pulley block (the nipper). Again, the device was designed to operate alongside a lead and line. In this case, the buoy would be pulled behind the ship and the line threaded through the pulley. The lead could then be released. The buoy ensured that the lead fell perpendicular to the sea floor even when the ship was moving. The spring-loaded pulley would then catch the rope when the lead hit the sea bed, ensuring an accurate reading of the depth. Both Massey and Burt’s machines were designed to operate in relatively shallow waters (up to 150 fathoms).

The Board of Longitude, mentioned above, was established in 1714 in circumstances as described here which led eventually to another navigational aid, the chronometer. A hundred and sixty years later in 1874, William Thomson, who became Lord Kelvin, and inventor of note, succeeded in sounding to a depth of 2,700 fathoms, over three miles.

Into the 20th century, our third device was geared towards greater depths, and proved to be a reliable deep-sea sounding machine, a motorised machine. Called a Submarine Fathometer, it was invented in 1923 and patented by an American, Dr. Herbert Grove Dorsey, and although with similarities to the traditional sounding line, used a much heavier weight suspended on a piano wire.

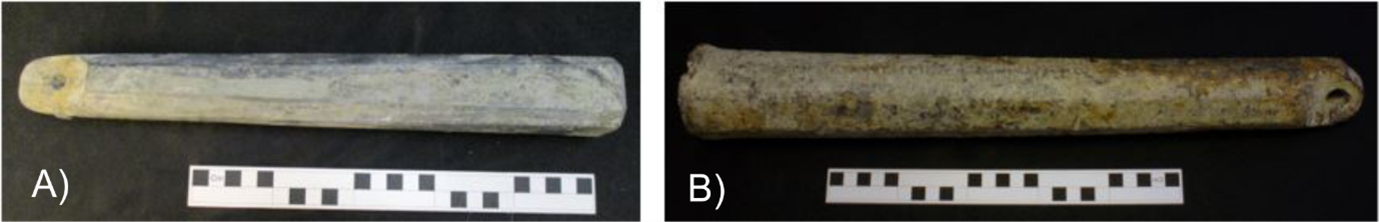

Plummets or sounding weights, Figures 5A & 5B, have been recovered from many shipwrecks, including two displayed at the Shipwreck Centre and Maritime Museum at Arreton Barns on the Isle of Wight:

Figure 5.A : Lead Sounding Weight from HMS P.12, 5.B: Sounding Weight from SS Londonier, Maritime Archaeology Trust

HMS P.12 was a Royal Navy Patrol vessel, built at Cowes in 1915 and lost on 4 November in a collision near Culver Cliff which is on the SE side of the Isle of Wight. SS Londonier was a Belgian registered steamship sunk by enemy action south of the Isle of Wight on 13 March 1918.

And finally, sounding weights from two recently discovered wrecks, NW68 and NW96, lost on the Shingles Bank NE of the Needles lighthouse, in the 17th and 15th or 16th centuries respectively. Both wrecks are now Protected and highlighted here. The lead from NM68 features as a Sketchfab model .

Further reading:

The video https://youtu.be/Eblwe2dQhDE gives a good historical summary of the early developments.

Testing the Waters: The Role of Sounding. Weights in Ancient Mediterranean Navigation. https://web.uvic.ca/~jpoleson/Sounding%20weights/Oleson%20Sounding%20Leads.pdf This is a learned treatise and for the aficionado.

Admiralty Manual of Hydrographic Surveying – https://archive.org/details/amiralty-manual-of-hydrographic-surveying/mode/2up An extension to sounding, into maritime surveying and is for those with a keen interest in the Admiralty’s role on the subject. Dated 1948, it is downloadable in different formats.