What do you know about Jute? MAT volunteer Roger Burns relates the tale of the wreck of the SV Alcester on the notorious Atherfield Ledge in 1897 and gives insight to the then importance of jute and its uses.

Launched on 8 October 1883 by Russel & Co., of Greenock for Haws, Lawson & Co., of Liverpool, the Alcester was an iron-hulled 3-masted sailing ship, measuring 78.33m long with 11.64m beam. During the after-launch ceremonies, it was claimed that the vessel would be capable of carrying 2,500 tons of cargo at 14 knots, according to the Greenock Telegraph and Clyde Shipping Gazette of 9 October 1883. The Alcester sailed to Rangoon for its maiden voyage, and other ports called at subsequently included Liverpool, Cardiff, London, Newcastle, Middlesbrough, Dundee (with jute), Calcutta, Hamburg, Bremerhaven, Invercargill, Bluff (N.Z.), Batavia, Cheribon, Fayal, Mauritius, Seychelles, Caleta Buena, and Valparaiso. One of many trips from Calcutta to Dundee was via Thurso, arriving in March 1892, the ship having traversed the Cape of Hood Hope after having experienced a cyclone near Mauritius; on this trip, the Alcester was carrying 12,791 bales of jute, reported in the Dundee Courier of 23 March 1892 as being the largest cargo it had carried to date.

On 19 February 1897 en route from Calcutta to Hamburg with a cargo of 2,360 tons of jute and 130 tons of water ballast, the Alcester went aground on Typet Ledge, which is part of the Atherfield Ledge, a major shipping hazard, off the Isle of Wight. About 170 shipwrecks are listed along the south west facing coast of the Isle of Wight between Blackgang and Afton Down, Freshwater Bay. Atherfield Ledge, Figure 1, is approximately 4km north west from Blackgang.

The Alcester had departed Calcutta on 2 November 1896 with a crew of 23 and was commanded by Allison Davie Haws who was related to the then Managing Owner, R.C. Haws of Liverpool. The voyage was uneventful and the master in the early morning of 19 February 1897 had the light of Start Point abeam and proceeded; up to about 3.30pm., the visibility in hazy conditions had been about four to five miles although out of sight of land, but then changed to dense fog and having made course adjustments through the day expected to hear the fog signal at St Catherine’s Point allowing him to set course for Hamburg. However, his dead reckoning was incorrect and having assumed that he had passed St. Catherine’s Point, he altered course but went aground, driving onto Typet Ledge shortly before 5pm. The Atherfield lifeboat, the Catherine Swift, was launched two hours later but Laws, the captain, declined help, asking for tugs, one arriving at 9pm. In the meantime, the flood tide was beginning with a swell, and the Alcester, some 1¼ miles off shore, bumped on and off the rocks. The tug tried to drag the Alcester back off the rocks, but it only became wedged on the rocks, three hawsers snapping in the process. Eventually, the hull gave way, and started making water. A storm was brewing, so the tug departed, and the swell moved the Alcester slightly nearer the shore. The lifeboat, taking two trips, landed all the crew safely, leaving only Haws and his 1st Officer onboard. The water in the hold caused the jute to swell, forcing up the deck. The overnight storm caused the two men great concern for their lives, signalling for the lifeboat, and both were saved at 8am. By now, the Alcester was broadside onto the coast and beginning to break up.

The circumstances of going aground were the subject of a Board of Trade formal enquiry, which concluded that Captain Daws was guilty of careless navigation and his Certificate of Competence was suspended from 11 March 1897 for three months.

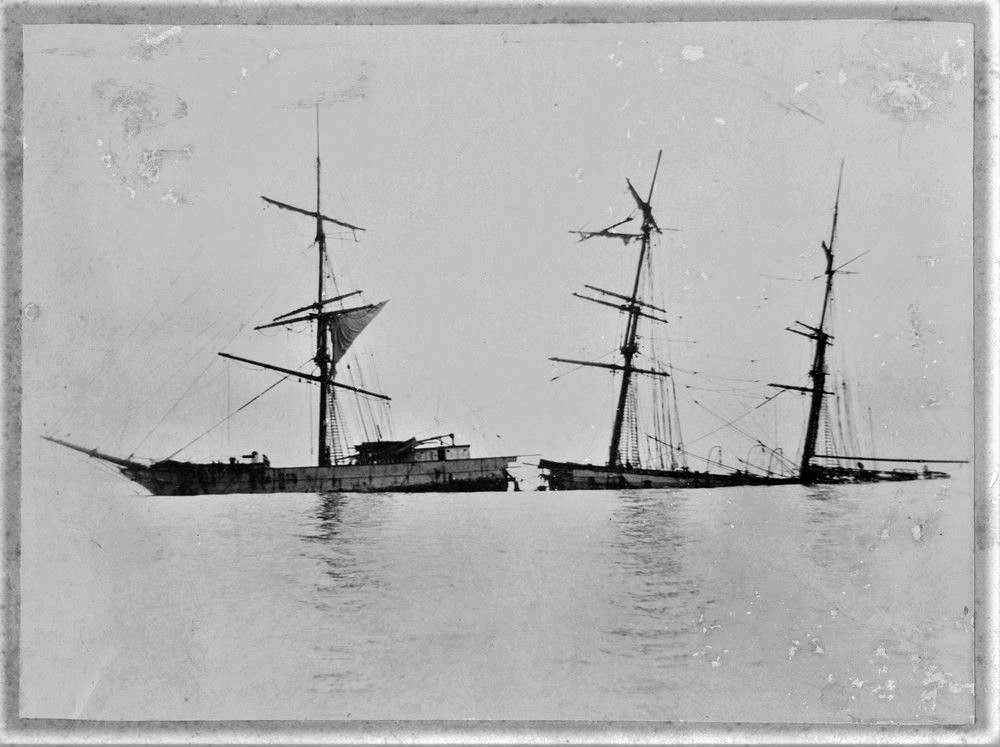

When Haws and the 1st Officer were landed, they reported that the deck had been raised further, and hatches, pilot house, boats and some cargo had been washed away, and that the cabin and forecastle were gutted. The Alcester was considered a total wreck, and the wind was strong SW with heavy seas. Later in the day, the 21st, the Alcester was breaking up, the maintopgallant-mast was carried away and wreckage coming ashore. The next day, the sea was breaking over the vessel which had parted amidships by 6m as can be seen in Figure 2. A large quantity of the cargo had been washed away, but some had been salved. By the 23rd, the weather had turned fine with smooth seas, facilitating salving of sails, hawsers and sundry gear. By 2 March, the aft part of the ship had broken up. A month later, it was assumed that a significant portion of the cargo was still aboard, and it was not until mid-April that the diving steamer, SS John Dixon, commenced operations lasting through to early May.

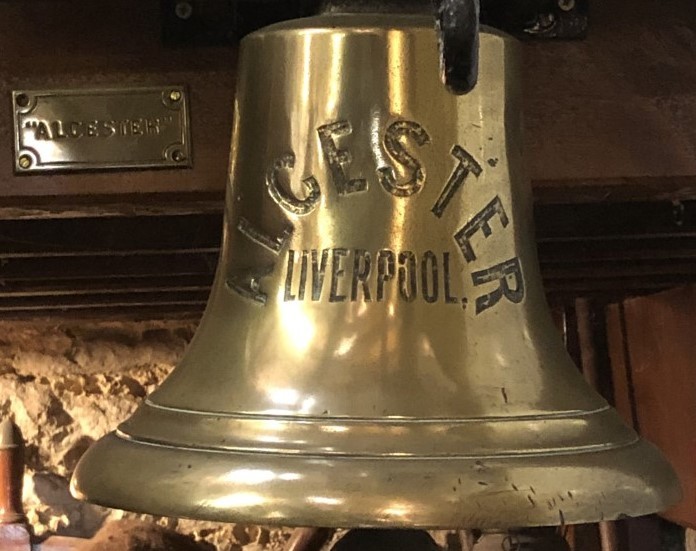

Artefacts from the Alcester on display at the Shipwreck Centre and Museum at Arreton, Isle of Wight, include its Bell, Figure 3, a Wheel Boss, Figure 4, and some salvaged jute, Figure 5.

What is Jute? The Verdant Works, a former jute mill in Dundee and now a museum, describes it thus:

“Jute is one of the most versatile natural fibres known to man. Raw jute fibre is obtained from two varieties of plant: Corchorus capsularis and Corchorus Olitorius, both native to Bengal (modern day Bangladesh).

During the 19th and early 20th centuries jute was indispensable. Its uses included: sacking, ropes, boot linings, aprons, carpets, tents, roofing felts, satchels, linoleum backing, tarpaulins, sand bags, meat wrappers, sailcloth, scrims, tapestries, oven cloths, horse covers, cattle bedding, electric cable, even parachutes. Jute’s appeal lay in its strength, low cost, durability and versatility.

Jute would come into the mill as a pucca bale weighing 400 lbs (c.181kg). Packed tight it would feel hard as wood. From here it would go through nine different processes, finally emerging from the mill as the finished woven product”.

Cultivation of the jute fibre is described here, which refers to an article in 1896 shortly before the loss of the Alcester. The raw fibres were exported across the world but Dundee became a World centre processing the fibres. Whaling was also a Dundee industry and it was discovered that whale oil was an important addition in the jute processing. These aspects can be read in full here and here and here.

A review of the British Newspaper Archive has jute in many articles but it is interesting to note that the Dundee Courier of 1 January 1897 includes a table headed “Latest Movements of Dundee Jute Fleet – in this table are listed ships bringing jute to Dundee, split into Left Calcutta, (14 ships), Left Chittagong, (2 ships), with a detailed summary of departure dates and latest position, and Arrivals at Dundee (22 ships). Between 2 October to 25 December 502,657 bales were imported, with most of the ships being steamers and five sailing vessels. Similar tables gave updates almost on a daily basis, such was the significance of jute for Dundee.

The jute industry in Dundee began to decline, but seventeen years after the Alcester was lost, the First World War saw a huge rise in demand, especially for sandbags made from jute, as they proved to be a life saver. “Certainly, millions of them found their way to the Western Front, 150 million of them from Dundee factories in just one two-week period in 1915. As a result, the Dundee jute industry – and the jute factories in India – made greater profits during World War I than in any period since the Crimean War”. [Cox, Anthony. Empire, Industry and Class: The Imperial Nexus of Jute 1840-1940. 2013. 108.] “Sandbags were usually filled, not with sand, but with whatever earth was to hand – often clay dug from new trenches that the bags were then used to line, two or three deep, in front (the parapet) and in the rear (the parados). ‘Trench lore had it that one bag would slow a bullet to half speed, and five were required to stop it cold.’ They mitigated the blast from an artillery explosion, but not the effect of a shell itself. The filling of sandbags was a frequent back-breaking task of army working parties”. [Persico, Joseph E. Eleventh Hour, Eleventh Day, Eleventh Month: Armistice Day 1918. World War I and its Violent Climax. 2007. 68.]

Looking at the jute, appearing somewhat mundane, in the Shipwreck Centre and Maritime Museum gives little appreciation of the historic importance of this produce, Figure 6, and which was also used in the Second World War Figure 7.