Have you given a thought as to how early mariners navigated? Specifically, how distance was recorded? Or how the “knot”, terminology for nautical speed, and the term “ship’s log” evolved? Or what a nautical spinner is? Here, volunteer Roger Burns investigates, and illustrates how knots and spinners are linked!

Evolution of the Humble Spinner

Mile and Nautical Mile Terminology

The “mile” has a variety of origins including from Roman times, mille passus, meaning a thousand paces. The Saxons had a slightly different length of pace and Britain developed regional definitions. In the early 16th century, maritime navigational instruments and parallels of latitude and meridians of longitude were being introduced, and, towards the end of the century, it was known in England that the ratio of distances to degrees was constant along a great circle, for example a meridian or equator. Robert Hues in 1594 wrote that the distance along a great circle was 60 miles per degree, expressing it as one nautical mile per arcminute. Hence, the term nautical mile was introduced. But the earth is an oblate spheroid, i.e. it has flattened poles, leading to minutes of latitude not being constant, approximately 1,861m at the poles and 1,843m at the equator. It was 1929 before international agreement was reached at 1,852m although it was 1954 and 1970 respectively before the USA and Britain adopted it; before that, the USA was using 6,0280.2ft. and the British Admiralty was using 6.080ft as the length of a nautical mile. The variations pre-1929 are explained here.

Speed at Sea

The knot (kn) is a unit of speed equal to one nautical mile per hour, and simple mathematics defines distance as speed x time. The key question back in the 16th century was how to measure speed over the water?

Prior to the nautical mile, a method attributed to Portuguese Bartolomeu Crescêncio, involved a sailor tossing a floating object attached to a line overboard and, using a sand glass, measured the time that it took to pass two points on the ship. This was commonly known as a “chip log”.

William Bourne (1535-1582), was an English mathematician, innkeeper and former Royal Navy gunner, whose credits included a design for a navigable submarine, and he was the author of the first known printed description of a log in his 1574 publication A Regiment for the Sea. Today, a log means a record of a ship’s activities but originally, it was terminology for part of a nautical speed measuring device. Bourne devised a half-minute sandglass used with a long line wound on a reel with knots tied in it at pre-determined intervals; a sailor would count the number of knots payed out from the reel in 30 seconds when the line was trailed from a vessel, and then multiply the number by two. In 1574, a mile was reckoned as 5,000ft., thus a ship would travel 42ft. in 30 seconds at one mile per hour.

Objects tethered to the log-line.

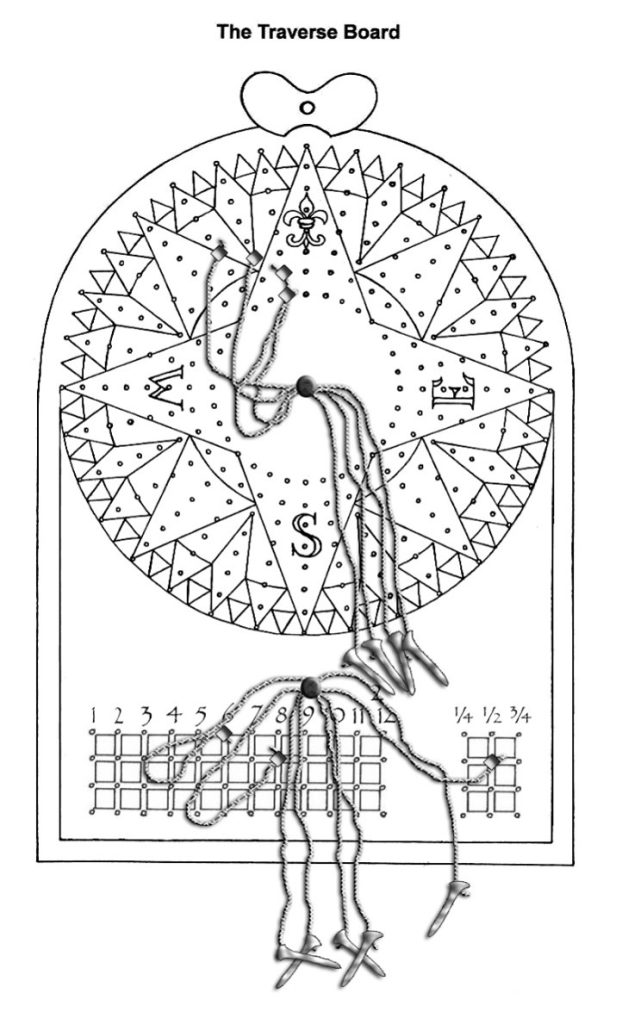

These evolved over time, one of the earliest being the chip log used with a traverse board, best explained by this video. This other video shows how the use of the chip log in conjunction with the traverse board to contributes to dead reckoning navigation – in this second video, a 28 second sandglass is used which was a known variation to the 30 second unit. Figure 1 illustrates a different design of Traverse Board but contains all the elements of the one in the video.

Figure 1: Traverse Board

SV Resolution, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

However, speed measurement was inherently inaccurate due to a number of factors, including the state of a following sea, the effect of currents, line stetch and time measurement due to temperature, humidity and sea state affecting the sandglass.

A variety of tethered objects with refinements made by different entrepreneurs came on the market and we look at one family’s contribution, Thomas Walker, his uncle and his son. Thomas Walker (1805-1867) started work at the age of 10 in the pottery industry than moved to printing where he devised a rubber system for printing, then as a clockmaker. He was inspired by his uncle, Edward Massey (1768-1852) who had invented and patented the Massey log. This was a device invented in 1802 and came into general use between 1836 and 1861; it comprised a rotating metal screw, Figure 2, which turned as the ship moved through water, the revolutions being registered on dials encapsulated in the part within the water, a significant improvement over the traditional wooden log. The three register wheels were within a metal box with a float on its upper side, the wheels recording fractions, units and tens of miles with a 100 mile capacity.

Figure 2: Massey Log, Source: Science Museum CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ,

Massey’s patent log consisting of two parts connected by rope, the rotator (or fly) with brass fins and an engraved brass recorder, patented and made by Edward Massey, London, England, 1854-1857. Materials: brass (copper, zinc alloy), copper (metal), manila and steel (metal)

Thomas and his son, Thomas Ferdinand Walker (1838-1921), developed Edward’s device into a number of improved versions. These included their Harpoon log, patented in 1861, which repositioned the dials into the rotator, reducing the bulk of the instrument. Father Thomas when he died left the business to his son, who continued with improvements, firstly the Walker Taffrail or Cherub log, followed in 1902 by the Walker Electric log.

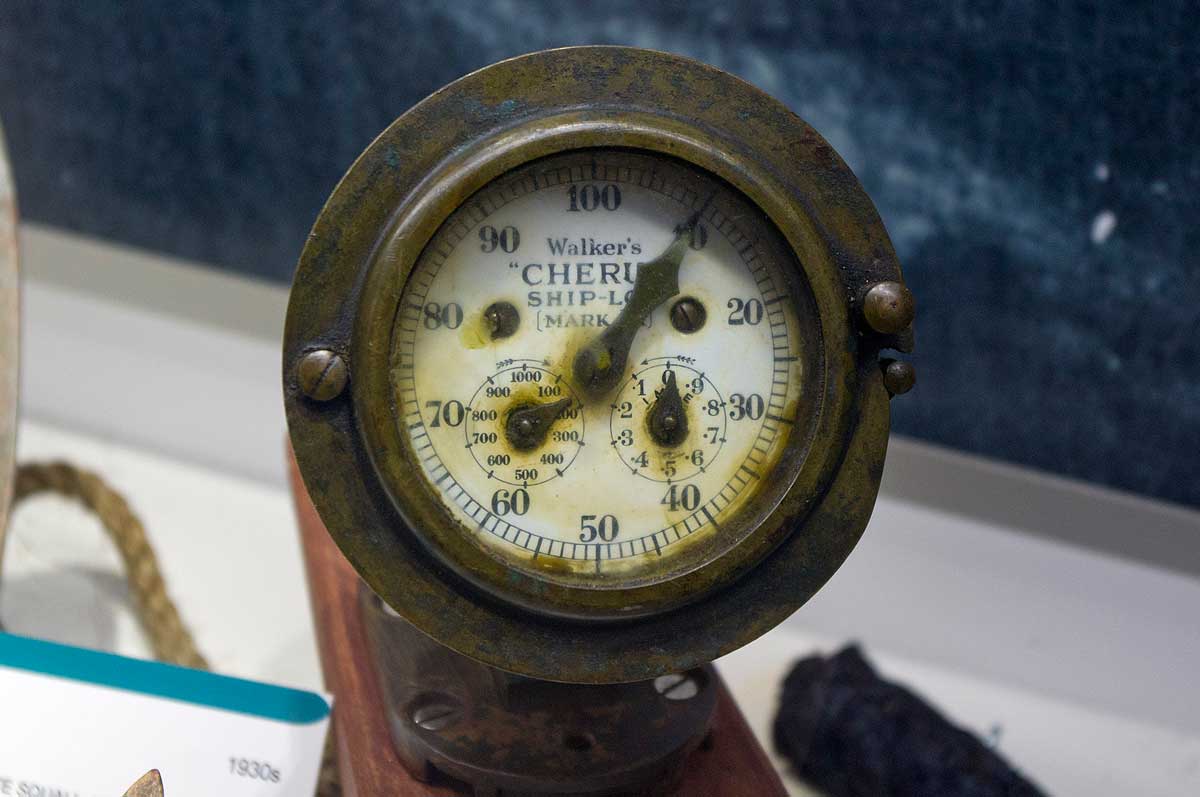

The Taffrail log, Figure 3, subsequently officially named the Cherub log, was a very significant improvement as it was designed such that it did not have to be hauled aboard to effect a reading. This log started in the 1880s, had 400 sales in its first year, and a decade later was selling approximately 2,000 per annum.

Figure 3: Walker’s Cherub Mechanical Log

Source: Skalavagr, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons. On display at Scalloway Museum

The Walker electric log could be read from several parts of the ship, including the bridge, and can be seen in use at elapsed time 05.05 and 06.36 in this BFI film, Mischief Goes South when passing the Needles, Isle of Wight.

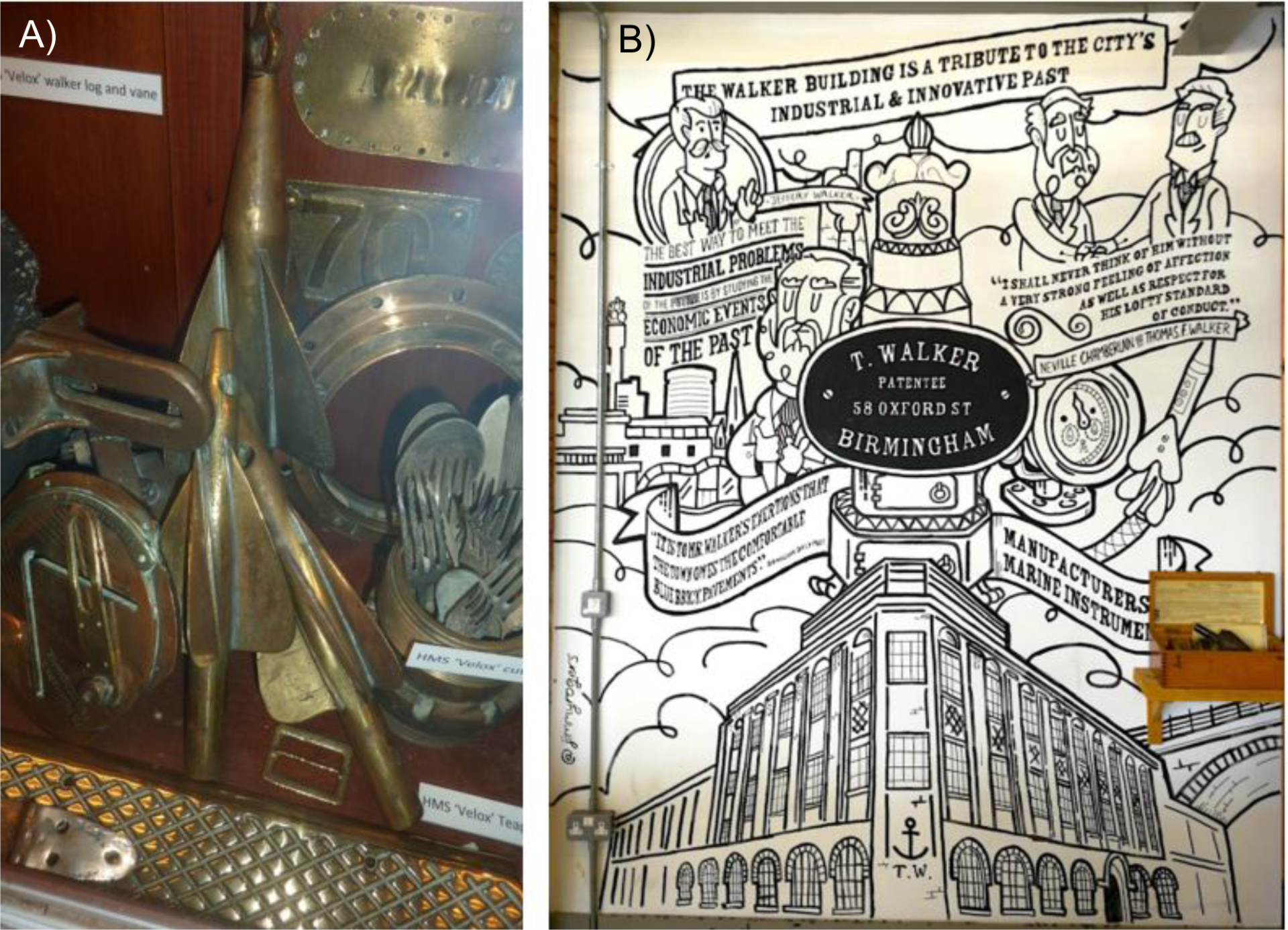

The component common to all the instruments after the Massey log is the rotating part in the water, referred nowadays as a log spinner, or just spinner. Several examples of spinners are on display at the Shipwreck Centre and Maritime Museum on the Isle of Wight, one being from HMS Velox shown in Figure 4A. The Walker spinners are stamped with the company name and includes their Anchor logo.

Figure 4A: Spinner from HMS Velox. Maritime Archaeology Trust.

Figure 4.B: Mural of Walker’s Building. Source: PJE Walker, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The firm, based in Birmingham, made other nautical instruments, was incorporated in 1902, acquired by Lilley & Gillie Ltd., and trades today under the brand name Walker Marine. There is a remarkable mural, Figure 5b, endorsed by Neville Chamberland and also showing the Anchor logo, celebrating where the firm was based in a building built for Walker in 1912 and which is now listed.