SWC volunteer, Roger Burns, explores the history of the sailing vessel Schiehallion, which was wrecked on the Isle of Wight in 1879, and one of the fascinating recoveries from the site – a collection of mysterious thistle-crested labels.

Introducing the Sailing Vessel Schiehallion

Schiehallion was an iron-hulled barque launched on 2 December 1869 in Dundee by Brown & Simpson & Co. for John Cruickshank, 26 Leadenhall Street, London, with co-owner George A. Ring of London. It was a relatively modest sailing vessel, 52.52m long with 8.6m beam, 602nrt and was completed quickly, as it sailed for London on 31 December 1869, having been registered in London with ON63548.

Schiehallion was destined for the UK/New Zealand trade, and its first commercial voyage was to Auckland. However, from there it called at Newcastle, N.S.W., then Hong Kong, Saigon (now Ho Chi Min City), Yokohama, Hong Kong again, Fuzhou, then New York before arriving back at Gravesend on 1 March 1872. Over the next seven years, it voyaged to and from the antipodes, calling at Lyttelton, Napier, Dunedin, Otago, Wellington and Canterbury in New Zealand, and Newcastle and Sydney in Australia. In late 1884 and early 1885 it called at Moulmein (Myanmar), Nagapattinam, India and Galle, Sri Lanka. All the voyages were to and from London, except on one occasion when it travelled to the Clyde in August 1875. Ownership changed in 1875 to Walter Savill, Leadenhall Street, London, and the vessel was adjudged to be in good condition, classed A1.

The Wrecking

Sailing from Auckland to London, Schiehallion went aground near Blackgang Chine on the Isle of Wight on 13 January 1879. It had set sail on 21 September 1878 with a crew of 16 and 13 passengers, seven of whom were children. The cargo of about 700 tons included casks of Kauri gum, casks of tallow, bales of wool and cotton, bags of cotton seed, silver plate, jewellery, candlenuts, ivory nuts, coconut oil, copra and manganese, which was insured for £16,115 (approx. £2.13m in 2021). The Board of Trade held an enquiry at which considerable debate centred on the course being kept from off Ushant up the Channel and the apparent lack of check observations and lead soundings.

The vessel ran aground at about 5.30am when fog was obscuring the Isle of Wight; the lighthouse at nearby St. Catherine’s wasn’t sounding its horn because the fog was at a lower level shrouding the land and the Schiehallion but not the lighthouse, which stood high above the see. It was 7am before the fog rose and the horn was started. In the meantime, the lighthouse keeper was unaware that the ship had gone aground.

When the vessel went aground on the rocks, it was deemed unsafe to launch the boats in the stiff south westerly wind. Despite the icy conditions, one of the crew, David Moore, a strong swimmer, swam ashore in the strong running seas with a line just reaching the shore, then hauled a hawser to shore anchoring it to rocks onshore. He did this with the help of Daniel Butcher, a man who had seen the vessel go aground and offered his assistance. The hawser was used by the others onboard to get ashore, hand over hand, women and children being assisted by the crew. Sadly, the second mate and a young boy apprentice were swept away by the sea and drowned; the others survived but lost all their personal effects.

The captain was John Levack, who had captained Schiehallion throughout its service life. He was also part-owner of the ship. The Board of Trade enquiry deemed Levack alone to be at fault due to aspects of his navigation and his Certificate was suspended for six months. Despite his 32 years at sea, (including 17 years as master), he was without previous casualty.

Just a day later, it was estimated that 200 cases of gum, 48 casks of tallow, 33 bales of cotton, and several bags of cotton seed had been washed ashore, with the prospect of more being saved. As reported in the Hampshire Advertiser of 26 July 1879, over 100 local fishermen brought an action for salvage in the Admiralty Division of the High Court, employed, they said, for almost two weeks, managing to save most of the cargo. An estimated £3,000 of cargo was saved. The cargo owners said that the value was only £1,275, offering £300, which was refused. Judgement was made in favour of the salvors for £430 with costs (£430 in 1879 is approx. £57k in 2021).

David Moore shunned the spotlight and soon got another post on the Isle of Bute to Auckland. He was tracked down and received the Bronze Medal of the Royal Humane Society for his bravery during a ceremony at the Theatre Royal in London on 15 October 1879.

Mysterious Artefacts

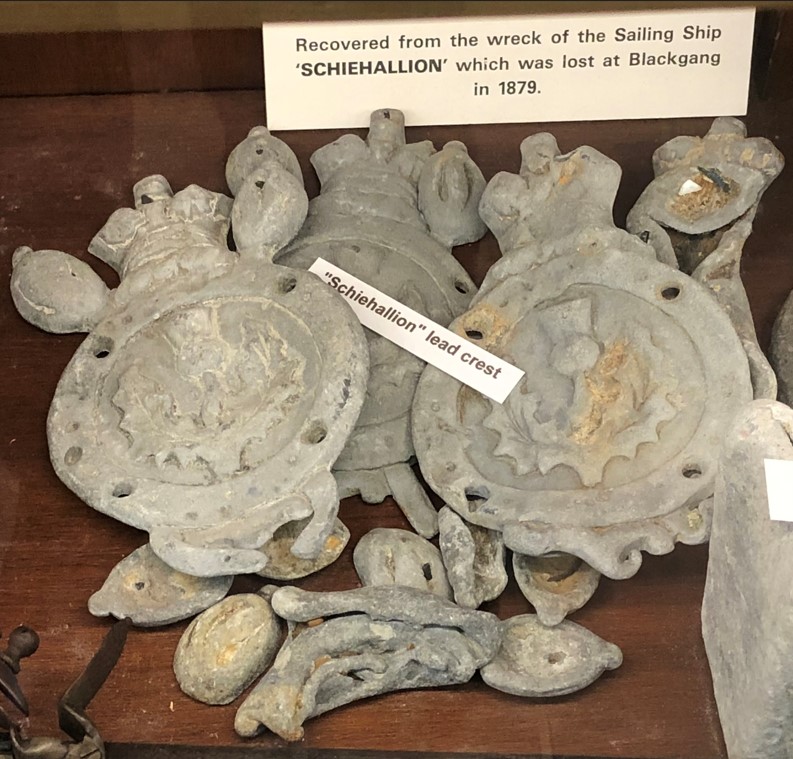

On display at the Shipwreck Centre & Maritime Museum is a set of artefacts recovered from the wreck, a collection of unusual lead “crested labels”, Figure 1. Some Kauri gum was also recovered.

The purpose of the crested labels has not been definitively discerned but Martin Woodward, owner of the Shipwreck Centre, confirms that they were found scattered and may have been decorative. They are generally 20cm long by 13cm wide, embossed with a thistle, flat on the plain reverse and have four holes, presumed to be for fixing them to a surface. Noting that the Schiehallion was Scottish built, named after a well-known Scottish mountain, and traded with New Zealand, which has a Scottish community, an approach was made to the National Museum of Scotland enquiring if the crests were recognisable. The principal technology curator kindly responded “They most closely resemble the ships badges from Royal Naval vessels, and I wonder if they may have been a decorative affectation of that sort on the Schiehallion. I can’t think of a practical application for them; however, they may have been a way of promoting the ship’s Scottish connections to the ex-patriot Scots in Australia and New Zealand”.

What do you think these crested labels from the sailing vessel Schiehallion were for? The Shipwreck Centre & Maritime Museum would love to hear from anyone who might be able to help with more information on their history. Please share your thoughts: