A 19th century Royal Navy Training ship, nearing home, lost in unexpected circumstances and one of the worst naval peacetime disasters. Not too unusual for maritime disasters you might think. But throw in the subsequent paranormal or ghostly sightings and the intrigue grows. Volunteer Roger Burns takes us through the events involving one such ship, HMS Eurydice.

Construction

This Royal Navy ship, ordered on 27 August 1841 was launched on 16 May 1843 at Portsmouth Dockyard as a 26-gun Fifth Rate Frigate. Designed by shipbuilder George Elliot, it was wooden hulled with a 42.978m gundeck, a 35.68m keel, 11.59m beam, depth of hold 2.667m, and it was 911 Burthen. A Full Ship rigged 3-masted ship with a design complement of 190 men, the guns were all 32-pounders, 18 on the Upper Gun Deck, 6 on the Quarterdeck, and 2 mounted on the Forecastle.

Interestingly, the Portsmouth Dockyard considered the Eurydice to be an experimental ship, intending to evaluate to what extent sailing qualities could be attained with a reduction of one-tenth of its draught. The ship was reputedly fast and, interestingly, had a very shallow draught to operate in shallow waters, evidenced by reference to drawings at the Royal Maritime Museum at Greenwich.

Service Summary

Eurydice was commissioned on 27 June 1843, serving the North American and West Indies stations. Recommissioned on 30 May 1846, it was deployed for four years to the South African station, then recommissioned again on 4 April 1854 for three years, initially in the White Sea during the Crimean war followed by the North American and West Indies station. There was a 20-year hiatus with no action although it was converted into a stationary, unrated training ship in 1861. In 1877, Eurydice was refitted at Portsmouth and by John White at Cowes, as a seagoing training ship, this role commencing on 13 November 1877 with a three-month tour of the West Indies and Bermuda. For this latter role, armament was revised to four of the original guns for training purposes.

The Loss of HMS Eurydice

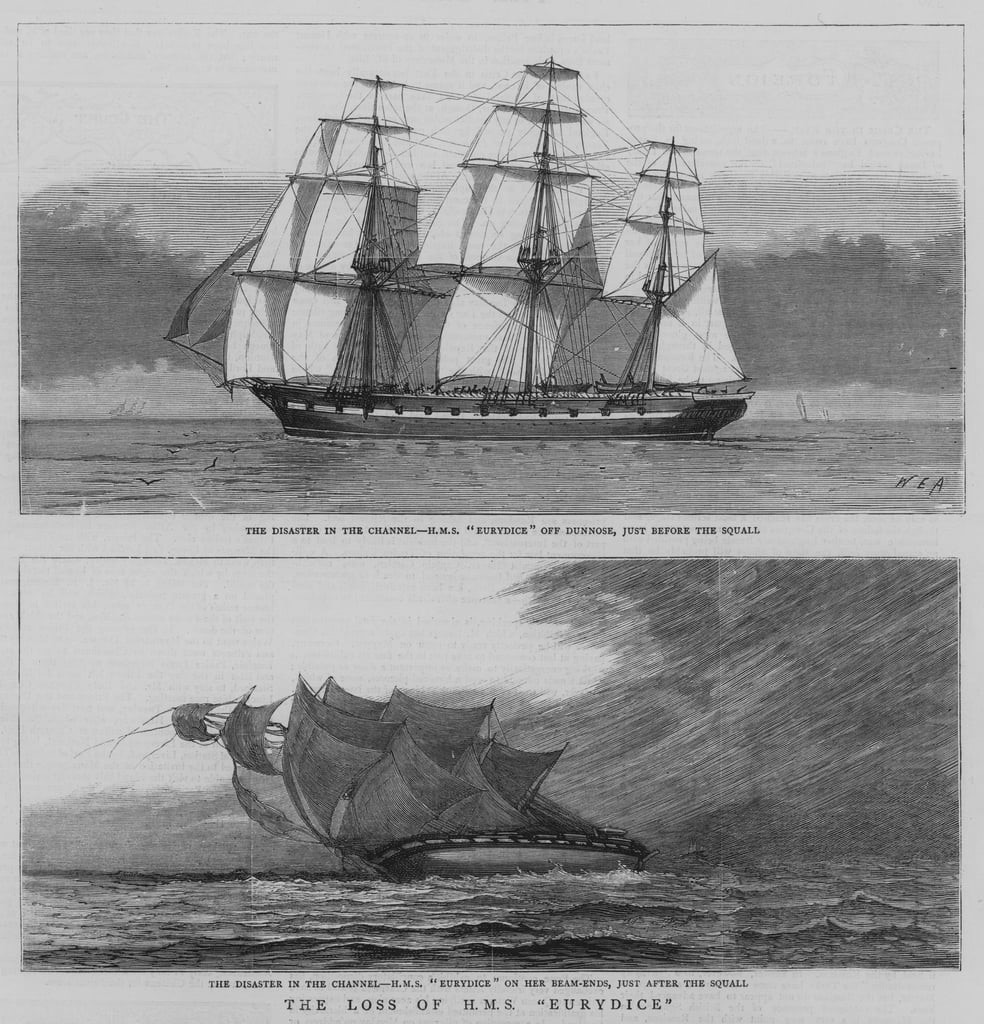

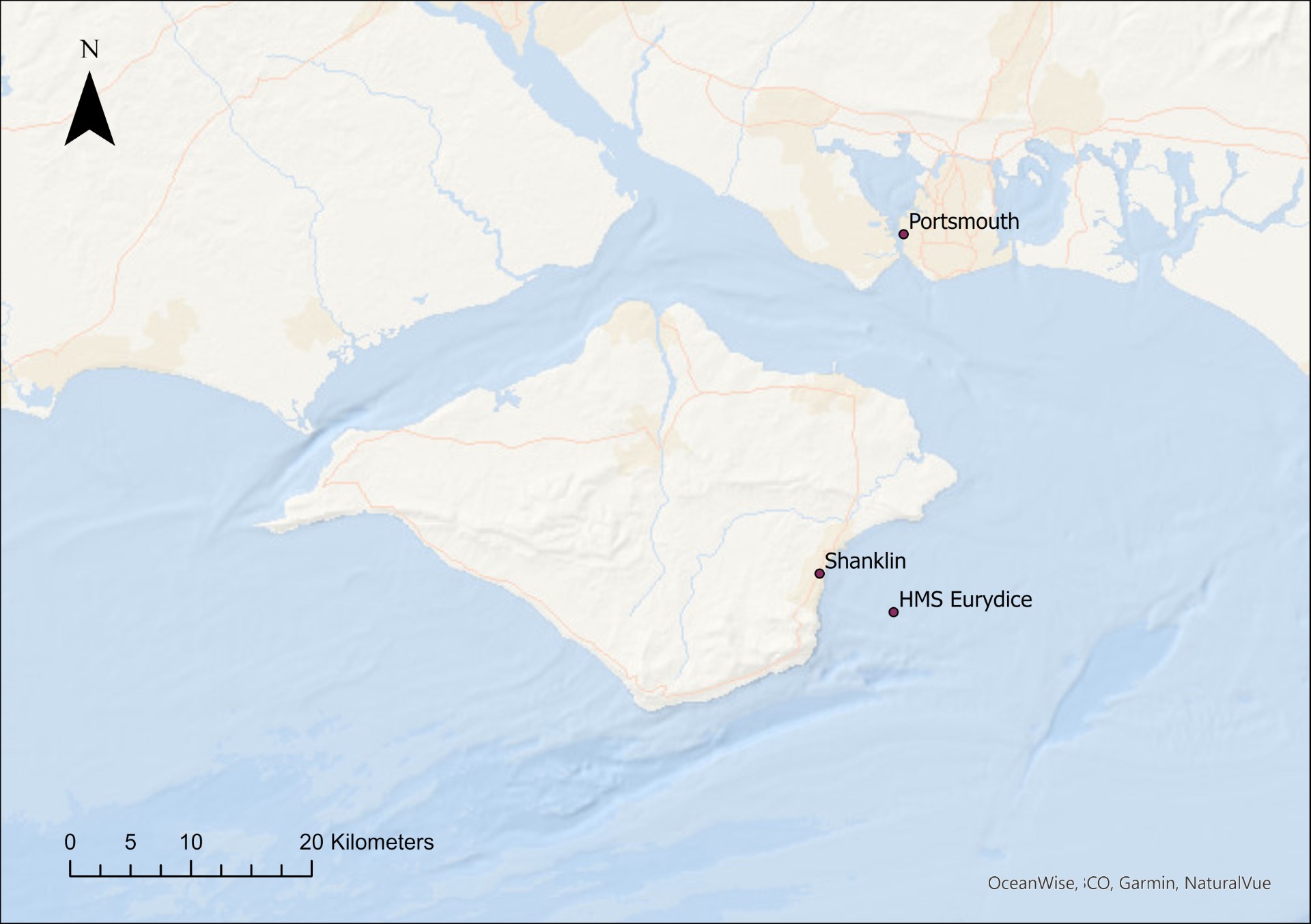

On 6 March 1878, the Eurydice departed the West Indies for Portsmouth. 18 days later, the Eurydice had reached Sandown Bay off the Isle of Wight and those on board were looking forward to setting foot in England. The weather, which had been kind, suddenly worsened, an unexpectedly intense and fiercely blowing squall with snow appeared in the Bay. Those on land witnessing the event thought that being so near to port, the apparent intention was to pass through the squall quickly, and according to witnesses on land, crucially left its gun ports open. This omission contributed to its downfall. At about 16.30, the ship heeled over in the terrific wind exposing the open gunports to the sea which rushed into the ship, sinking it in 11 fathoms (c.20m) of water.

Figure 1: HMS Eurydice off Dunose, IoW, just before the squall, and after on its beam end.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

William Edward Atkins, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. An illustration for the Graphic 30 March 1878.

Nobody actually saw the sinking due to the snow but as soon as the visibility cleared, the wind dropped and the upper masts could be seen. One of the post-event witnesses was nurse Mary Stoner, Cuckfield’s District Nurse for many years, who had gone to Sandown on a working holiday with her employer, Major and Mrs Sergison, and there she saw the wreck. Another witness was the 3½ year old Winston Churchill living at Ventnor at the time.

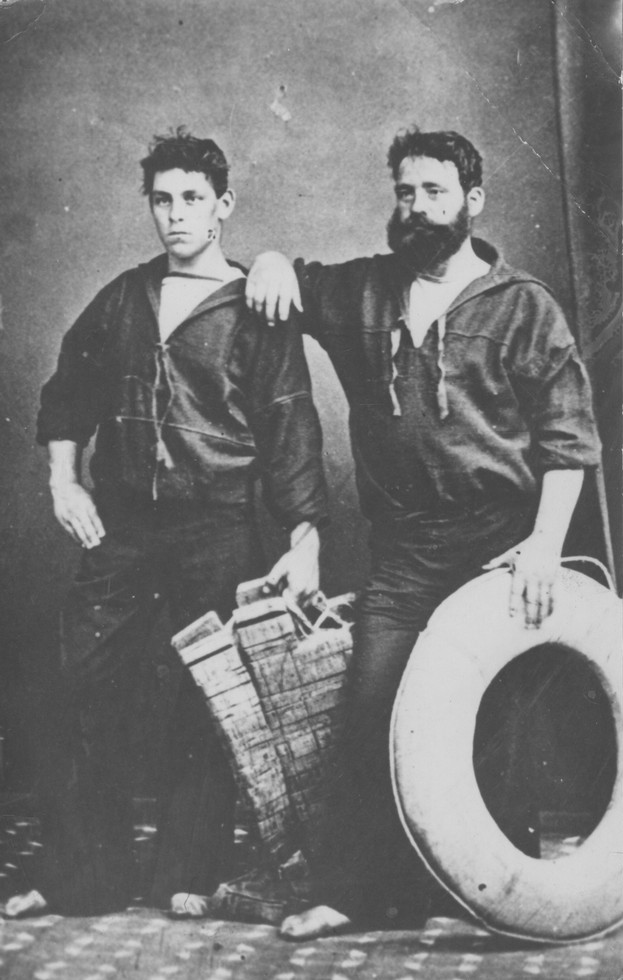

There were only two survivors from the 334 on board, Sydney Fletcher, a 19 year old, and Benjamin Cuddiford, and they were both called at the inquest of three of the crew, held at Ventnor on 27 March 1878. Evidence included the circumstances prior to the loss and the 13-man jury heard that all the sails were set as they approached the Isle of Wight, and as the weather changed, the lower stunsail (studdingsail) was lowered as the wind increased, followed by orders to take in the royals which were lowered but not furled, then orders to let go the top-sail halyards and the main sheet. However, the water was now up to the crew’s waist on the starboard side. The ship was on its beam ends, the keel and sail visible in the water, and began sinking forwards. The sudden gust had been unexpected and such a quick storm had not been previously experienced. Witness said that it was not unusual on a Sunday for gun ports to be open to let in fresh air. A subsequent Enquiry concluded that those on board were not to blame, the sudden change in the weather turning so quickly and violent being the culprit

Figure 2: Postcard – The only two survivors, Sydney Fletcher & Benjamin Cuddiford

Courtesy of the Trustees of Carisbrooke Castle Museum: ref NETCC : P.1986.1683

Raising HMS Eurydice

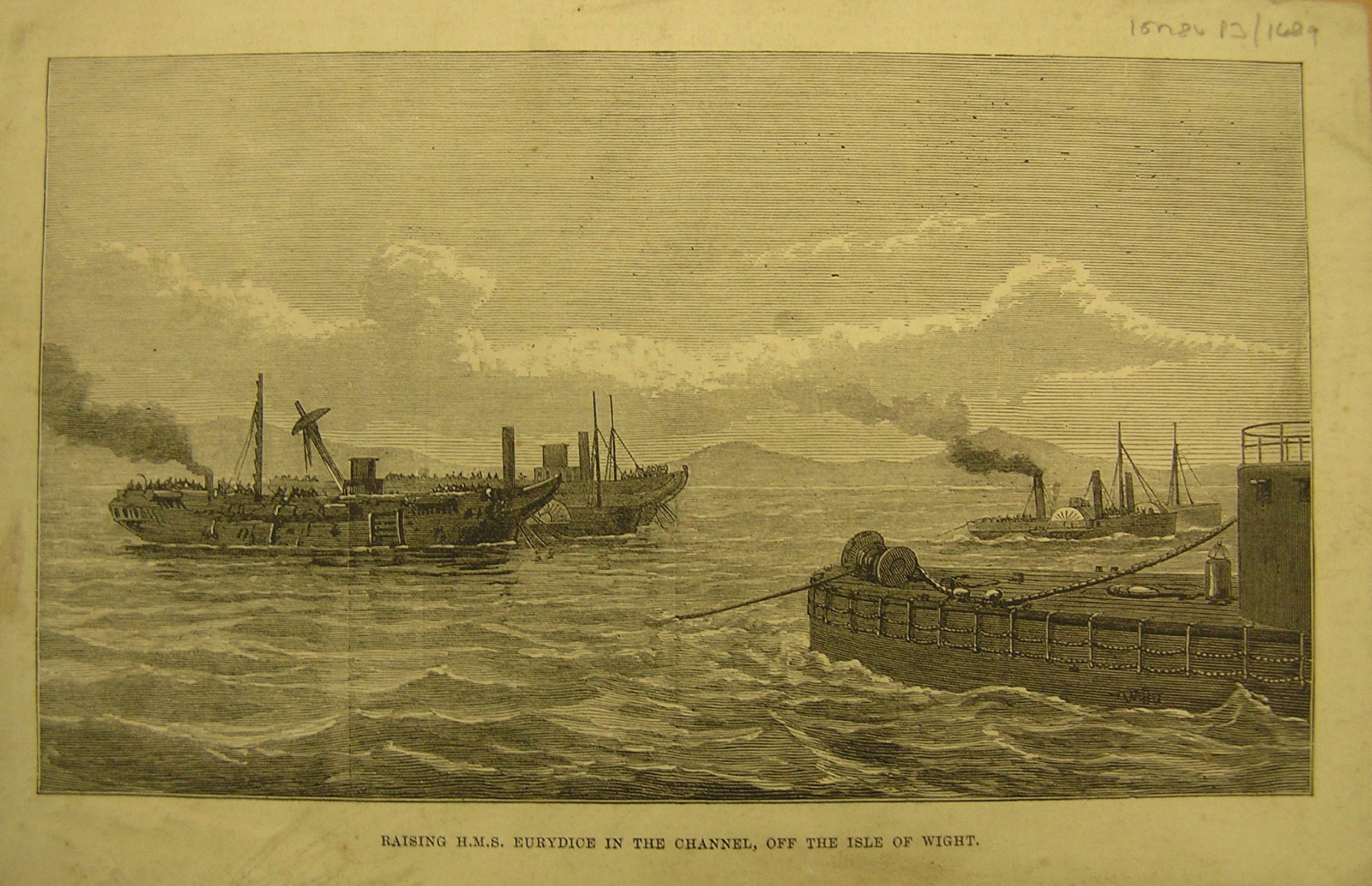

Divers and riggers attended the wreck and removed the top rigging and several attempts were made to float the Eurydice but leaks were found more prevalent than expected. Persevering, the leaks were sufficiently sealed by the divers to allow the wreck to be taken to Portsmouth.

Figure 3: HMS Eurydice sinking location off the Isle of Wight

Maritime Archaeology Trust

Eventually on 2 September 1878, with the naval tugs Manly, Samson and Malta surrounding the Eurydice, and hoses from their steam pumps on the deck of the Eurydice, pumping was commenced when low water was at 07.30, and by 10.00, floatation was achieved. The tug Grinder then took the Eurydice in tow and slowly moved to Portsmouth with the three tugs keeping station alongside, eventually berthing the Eurydice in the north corner of the Dockyard, alongside a hulk named Laurel. The Eurydice was found too badly damaged to be returned to service and was later broken up.

Figure 4: Raising HMS Eurydice

By Kind Permission Hampshire Record Office: 15M84/P3/1489

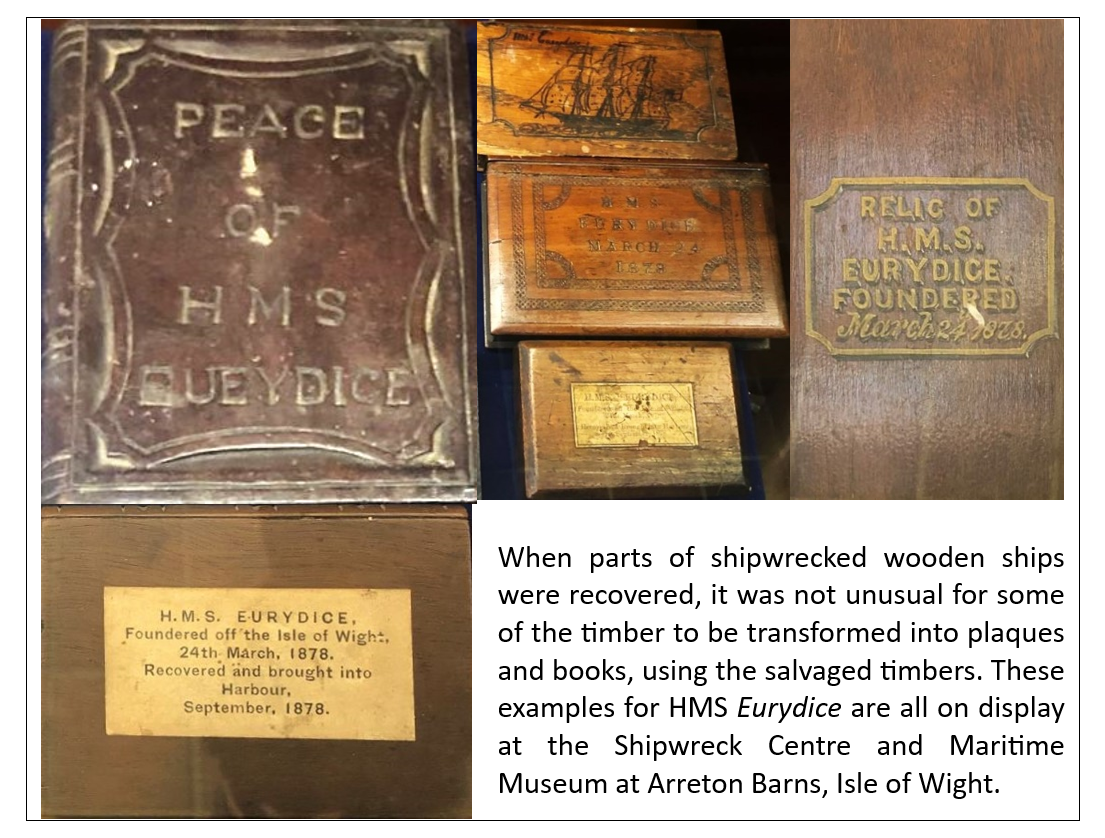

Artefacts

The bell from HMS Eurydice is currently hanging within the tower of St. Pauls church in Shanklin, Isle of Wight and is used for bell ringing.

Figure 5: Wooden plaques and books made from the ship’s timber

Poetry & Verse

Several poems were composed about the homecoming of the Eurydice. There are examples by ‘CRP’ and Harriet E. Phillimore held by Hampshire Archives and Local Studies, also one by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and another by Gerard Manly Hopkins. A ballad, but without the musical score, is held by the National Library of Scotland.

Memorials

Seven crew who died are buried at Shanklin Cemetery, Shanklin, more are buried at Christ Church, Sandown, and both churches include memorials. Naval memorials are at the Clayhall Royal Naval Cemetery in Gosport, and at St. Ann’s Church, in the Naval Base in Portsmouth. The Gosport memorial is Grade II listed, featuring Eurydice’s anchor with the names of the 364 crew who lost their lives inscribed on the four surrounding base panels.

Figure 6: Eurydice Memorial at Gosport

Maritime Archaeology Trust

Paranormal & Strange Happenings

Two years after the Eurydice was lost, its sister ship HMS Atalanta set off from Bermuda and was never seen again.

Over the years, sailors have sighted a phantom ship, thought to be HMS Eurydice. There is a story involving Commander F. Lipscomb of a Royal Navy submarine which took evasive action in the 1930s to avoid the ship, only for it to disappear. On 17 October 1998, Prince Edward reportedly saw a three-masted ship off the Isle of Wight while filming for the television series Crown and Country, and the film crew claimed to have captured its image on film. At that time, none of the local sail training organisations were at sea. You can learn more about these spooky sightings in the Maritime Archaeology Trust video Ghost Ships!

Ghostly sightings of ships like the HMS Eurydice are not isolated. Just two examples include the Mary Celeste and the Flying Dutchman. Others are summarised here and also here