MAT volunteer Roger Burns describes the loss of SV Clarendon which went aground off the Isle of Wight with most of those on board being lost, how some of its timbers were re-purposed on the Island, and how the tragedy led to the construction of a lighthouse and eventually two RNLI Lifeboat Stations.

SV Clarendon

The Clarendon was a wooden hulled 3-masted merchant cargo and passenger sailing ship built at Chepstow in 1823, surveyed by Lloyd’s in 1824 at Bristol, and classified as 11A1. The leading dimensions of the ship have not been found but it was rated at 307 tons burthen when built and 345 tons burthen when lost which translates to a relatively small ship. It was copper-bottomed in 1832, resurveyed by Lloyd’s at London in late 1835, and while the Lloyd’s record is in parts illegible, the condition was “good”, but its classification had changed to AE1. Too early for formal registration, the Clarendon “belonged to London”, the owner when surveyed Taylor Fry & Channel, the captain was Whitsong, and its intended destination after survey was Nevis & St Kitts. Referred to in records as a “West Indiaman”, it is highly probable that the Clarendon undertook repetitive voyaging to St Kitts and the other Caribbean islands, especially as previous ships of the same name were also West Indiamen with similar destinations.

The Disaster

Departing Basseterre-roads, St. Kitts on 27 August 1836 for London, the Clarendon was now owned by Manning, Henderson and Lethbury, under the command of Samuel Walker, carrying a cargo of rum, sugar, molasses, coconuts, peppers and cedar. Differing sources record either 16 or possibly 17 crew, and 11 passengers. Heavy weather in the Atlantic battered the ship, and it passed the Lizard on 6 October, but continuing and increasing gales forced the ship closer to land, eventually going aground at 6am on 11 October 1836 broadside on the south-west beach just east of Blackgang Chine, Isle of Wight. The ferocity of the waves together with Clarendon’s broadside direction rolled the ship, the masts striking the beach with such force they snapped and within 10 minutes the ship broke up. Bystanders on land, alerted by rockets, who were witnessing this destruction were powerless to intervene but an ex-naval man, John Wheeler, braved the sea with a rope lashed around him, held by one of his mates and plunged into the water, calling for those on board to jump into the sea – James Harris, second mate who had been shipwrecked on four previous occasions, and seamen William Burney and John Thompson did jump, lashing themselves to some spars, and were pulled successfully ashore. Tragically everyone else on board were lost, including many who had taken shelter in the poop which was washed away, and most of those lost were entangled in the rigging or struck by the falling masts and rigging. Those bodies which were found were washed ashore on the Island except, apparently, Miss Gourley’s body which was carried to the bottom of her father’s garden in Southsea! By a remarkable coincidence, John Thompson had saved John Wheeler four years earlier when both served on Lord Yarborough’s yacht, the Falcon.

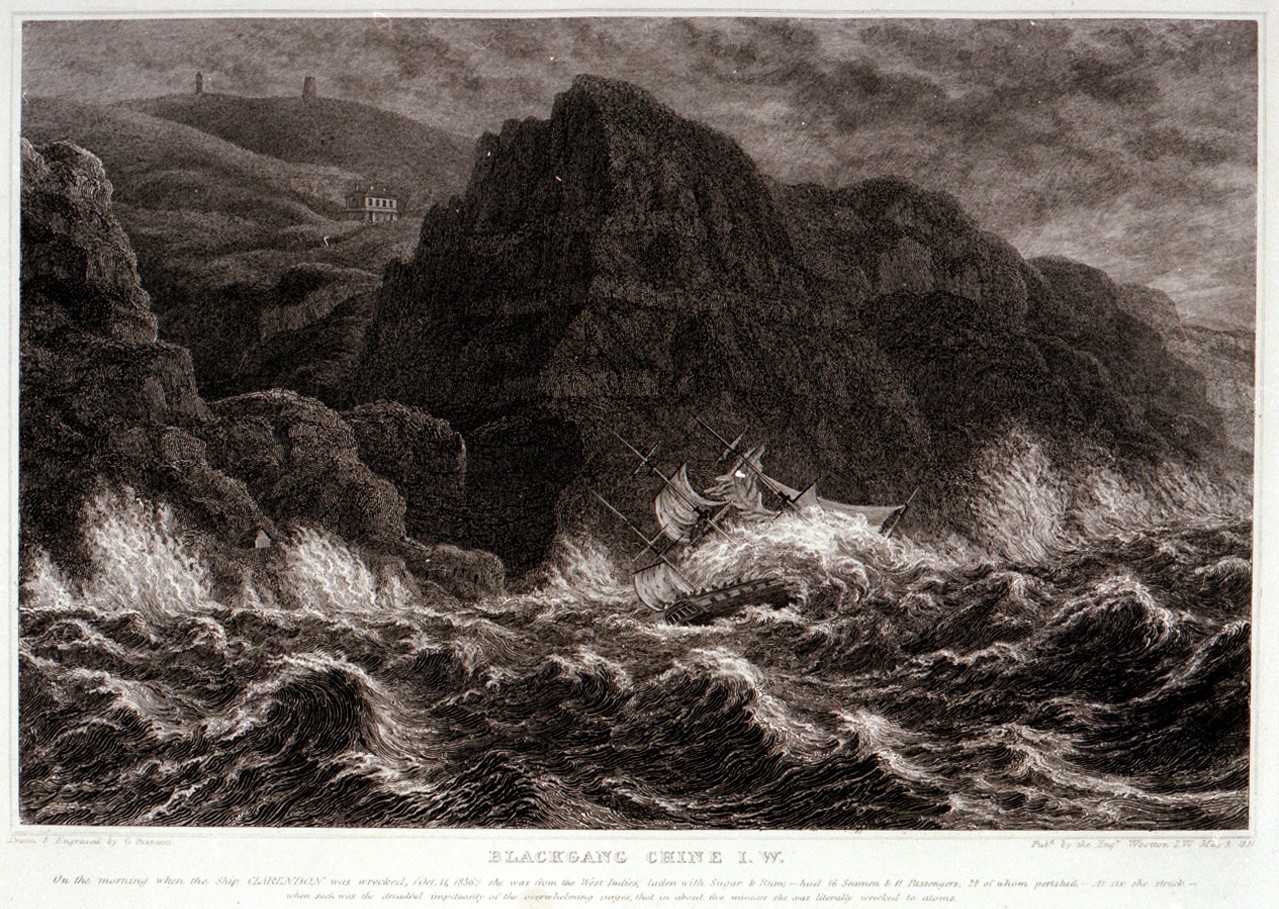

Figure 1: SV Clarendon ashore on the Isle of Wight. Source: https://bit.ly/ClarendonBrannon

Brannon, G (artist and engraver), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. The image is of an engraving dated 9 May 1837 etched and published by G. Brannon, an Isle of Wight resident, and now held by the Royal Museums, Greenwich. A copy is also on display at the Shipwreck Centre and Maritime Museum at Arreton Barns, Isle of Wight.

The passengers included Lieutenant Shaw (Shore in some references), 14th Regiment, his wife Amelia and four daughters aged 9-months to 18 years named Mary Ann, Caroline, Jane and Emily, their servant George Higginbottom, Walter Pemberton and his 12-year-old daughter Lebecca, a miss Margaret Gourley from Portsmouth, and a Mr Charles Shepherd from Exeter. 25 on board lost their lives, and 18 are buried in Chale churchyard. Some bodies were never found. Lt. Shaw had joined the 74th Regiment as a young ensign, distinguishing himself in the Peninsula war and was severely wounded, then he was in the 84th Regiment, and then exchanged with the 14th serving in the West Indies. Pemberton was a wealthy planter, and his daughter was a Creole coming to England for her education. Miss Gourley was the daughter of an officer’s widow.

The cargo and the ships timbers were strewn along the coast, with little being saved. 14 bodies were washed ashore and an inquest was held on 20 October under the coroner Benjamin Neasdale. The jury assembling at the Carisbrooke Castle inn and once sworn in, travelled to Chale church to view the bodies several of which were bruised or mutilated from the pounding of the sea and having been struck by wreckage. The principal witness was second mate Harris who related the whole episode and recounted how Captain Walker really expected to reach St. Helens. The crew were identified as James Penny, Robert Smith, Thomas Johnson, William Sherlock, Edward Cousins, William Stewart, John Graham, Edward Rush, Timothy Isee, Thomas Stratton, Joseph Hall, and James Paris. The jury returned a verdict of Accidental Death for all of the deceased, and some of the bodies were buried at St. Andrew’s Church at Chale the old registers of which from 1699 includes those from the Clarendon as well as from several other wrecks.

Material from the Clarendon

On 22 October 1836, five persons were sentenced for plundering the Clarendon wreck with varying punishments, varying from six months hard labour or £20, two months imprisonment or £5, one month imprisonment, and one case of a 15s (=£0.75) fine. However, the authorities had salved some material, offered for auction on 27 October in Newport, comprising three tons of excellent cordage, 200 yds (c. 183m) canvas, 90 fathoms (c.165m) of both 5ins and 6ins (c. 12.7cm & 15.24cm) hawser, a large quantity of oak timber, blocks and chains. Later, two items, a pistol and snuffer, were recovered from the Island’s south coast, and were said to have come from the Clarendon.

Some of the timbers found their way to form part of an inn subsequently called the Clarendon Hotel, renamed the Wight Mouse Inn, and some pieces of wood and a spar were displayed at Blackgang Chine theme park.

According to the Hampshire Telegraph on 23 October 1836, some of the rum from the Clarendon was saved and was sold for 6d per gallon, exclusive of duty (c.£1.99 in 2021).

Public Opinion and Outcome

The Islanders were not immune to salving wrecks, a common occurrence, but this disaster troubled many due to its severity in such a short time, and saving lives became a greater priority.

Public pressure on Trinity House led to a lighthouse, Figures 2 and 3, being built during 1937-1838 but due to being “capped” by mists and fog could often not be seen by mariners, so the lantern was lowered. The history of the lighthouse can be read here which was first used on 25 March 1840. Additionally, two RNLI lifeboat stations along the South west facing coastline were eventually built in 1860, at Brighstone Grange and at Brook.

Figure 2: Aerial View, Lighthouse Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/c6/St_Catherines_lighthouse_and_Point_-_geograph.org.uk_-_80736.jpg Tony Scott / St Catherine’s lighthouse and Point. CC BY-SA 2.0

Figure 3: Elevation, Lighthouse Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/6e/St._Catherine%27s_Lighthouse_23.jpg Simon Burchell, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

It often takes a disaster of significant extent to change the mood of public opinion, and although tragic for those on board who lost their lives within minutes of going aground and tragic for their families, the ensuing lighthouse and RNLI lifeboat stations doubtless saved many lives of mariners in future years.