Rigging Blocks are essential items on any vessel where heavy or otherwise inaccessible items need moving or adjusting, such as sails and cannons. Volunteer Roger Burns discusses their manufacture and essential components with particular reference to those provided to the Royal Navy in the second half of the 18th century by Walter Taylor of Southampton.

The Taylor Family & Initial Development

Walter was born in 1734, and his grandfather, and father, who had married Elizabeth née Shiver from Whippingham, IoW, were also called Walter, and were known as master carpenters in Southampton; this skill was a key attribute in the successful business Walter and his father developed in making wooden rigging blocks and subsequently pumps for the Navy. His father had served at sea for a period and was aware of significant difficulties in operating these blocks, hand-made by tradition. There were many rigging block makers, and his father, on returning to Southampton, investigated locally based makers as to how these were made. Meantime, Walter, aged 14, had been apprenticed to a Mr. Messer, a local ship’s block-maker in Westgate Street, Southampton. Messer died in 1754 and the Taylors acquired the business, setting about the improvement and reliability of rigging blocks. These premises were inadequate and they acquired nearby premises, installing a horse gin which powered belt driven machinery.

Rigging Block Construction

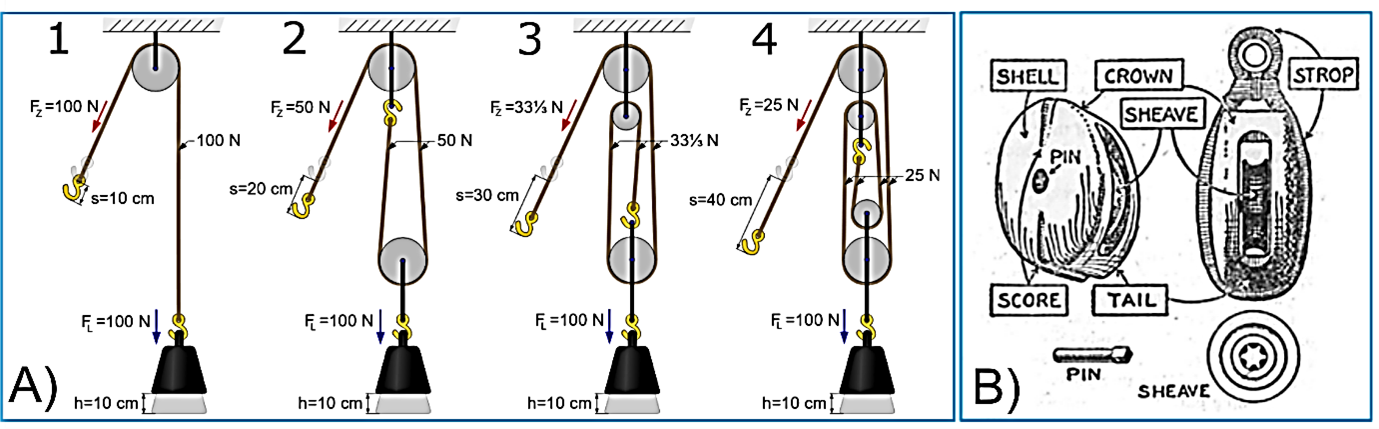

The sails of vessels such as 19th century full-rigged ships could weigh several tons and even some individual sails were too heavy to adjust without mechanical aids. The term Mechanical Advantage – the ratio of the force exerted by a machine to the force applied to it – is key in lifting and lowering significant weights and is illustrated in Figure 1A displaying single or multiple pulley wheels. More pulleys decreases the necessary force, but increases the distance required to raise a load the same amount as indicated, showing that four pulleys requires 25% of the force with one pulley. FZ = Rope tension or effort force, FL = Load or resistance force, s = Rope displacement (distance pulled) or effort distance, h = Height (distance load is raised) or resistance distance. Figure 1B shows the essential component parts.

Block Arrangement

Figure 1A: Explanatory Illustration of Mechanical Advantage. Source: Prolineserver, Tomia (minor edits by Stanisław Skowron, scale adjusted by Atropos235), CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons,

Figure 1.B: Andy Dingley (scanner), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

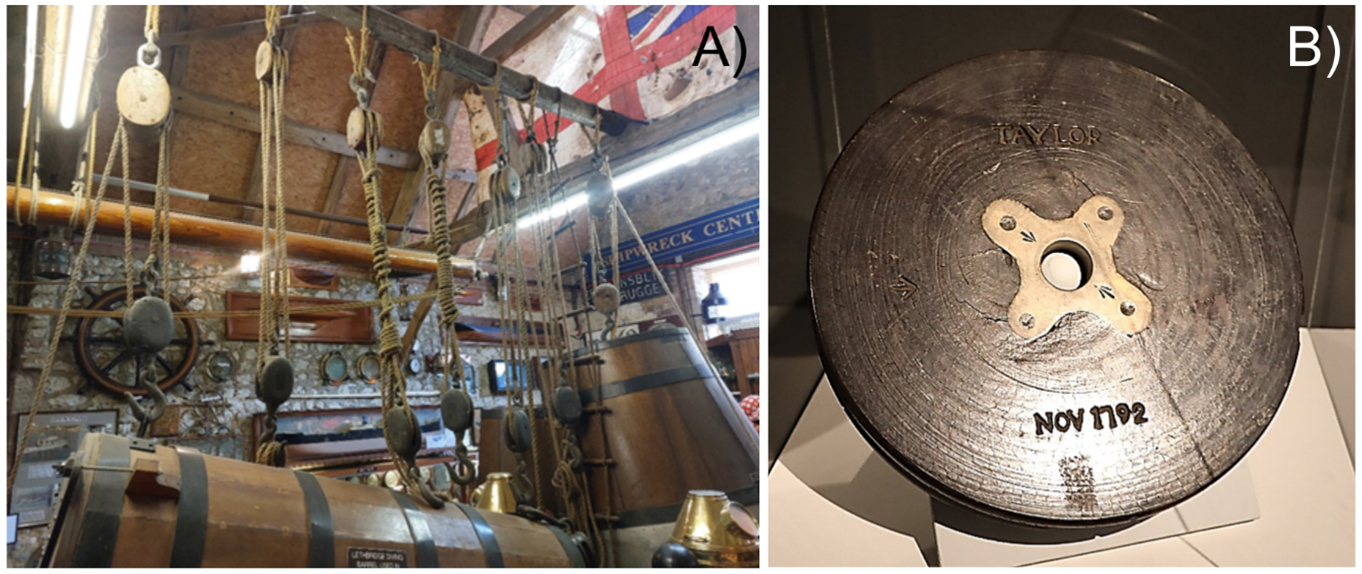

So for a Rigging Block, imagine that the requisite number of pulleys are housed together, and oriented accordingly to suit the task in hand, sailors applying effort to the “vacant” hook in Figure 1A to move the sail represented by the black weight. Figure 2A shows several pulleys and ropes on display at the Shipwreck Centre and Maritime Museum at Arreton, IoW. To reduce friction, lignum vitae was used for the sheave assembly, with a bored hole running on a turned pin, which Taylor substituted with an iron pin with later variations, as shown in Figure 2B. Father and son developed other refinements but importantly, and in parallel, developed machinery for accuracy and repeatability of component parts.

Suspended Blocks and a Sheave

Figure 2A – Display at the Shipwreck Centre and Maritime Museum

Figure 2B –Sheave stamped Taylor, made 1792 at Woodmill, Source: Geni, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Shipwreck Centre and Maritime Museum has several block components on display from the SV Henry Addington (1789), and while these may have been made by Taylor, conclusive evidence has not been found.

Contract with the Royal Navy

The local M.P., Hans Stanley, took an interest in what was then secretive work by Taylor, conducted so as to avoid others copying their developments. Stanley was also one of the Lords of the Admiralty and he suggested that the Taylors submit a set of their topsail blocks to the Admiralty, who needed at that time approximately 1,400 blocks for a 74 gun warship to handle sails and guns. These blocks were successfully trialled and the Navy expressed interest but there were doubters for using an external contractor. Naval experts visited the Taylors’ workshops and their fears were allayed, and the supply of 100,000 blocks per annum were contracted from 1759 with the Navy. Additionally, a Captain Bentinck considered a full test should be undertaken with all the blocks on his ship to be from the Taylors; this 1761-2 test clearly demonstrated that the smaller than hitherto blocks used not only reduced the weight just on the masts by some 1.3 tons, but were completely effective and cheaper. Bentinck and Taylor then drew up a schedule of reduced block sizes required for the different sizes of naval ships.

Remuneration from the Navy contract saved the business as Walter was declared bankrupt in June 1761 due to the costs incurred by his recently deceased father in developing their block design and the required machinery. Fully supported by his mother, the business survived and patents were taken out, one being dated January 1763, as reported thus in the Salisbury and Winchester Journal of 10 January 1763: “Whereas his present Majesty has been graciously pleased to grant his Royal Letters Patent, under the Seal of England, to the Executor of Mr. Walter Taylor, late of Southampton, deceased, for the sole making, vending, and supplying his Majesty’s Royal Navy, and others, with all Kinds of Ship Rigging, Gun Tackle, Shivers and Pins, in Iron, Brass, and Wood, upon Principles intirely new, and by Instruments, Engines, and Tools of the Invention of the said Mr. Taylor: This therefore is to caution all Persons not to pirate, imitate, make, or counterfeit, either the Whole or any Part of the said Blocks, Engines, Instruments, or Tools, used in the Construction thereof, on Pain of being prosecuted according to the Statute in that Case made and provided”.

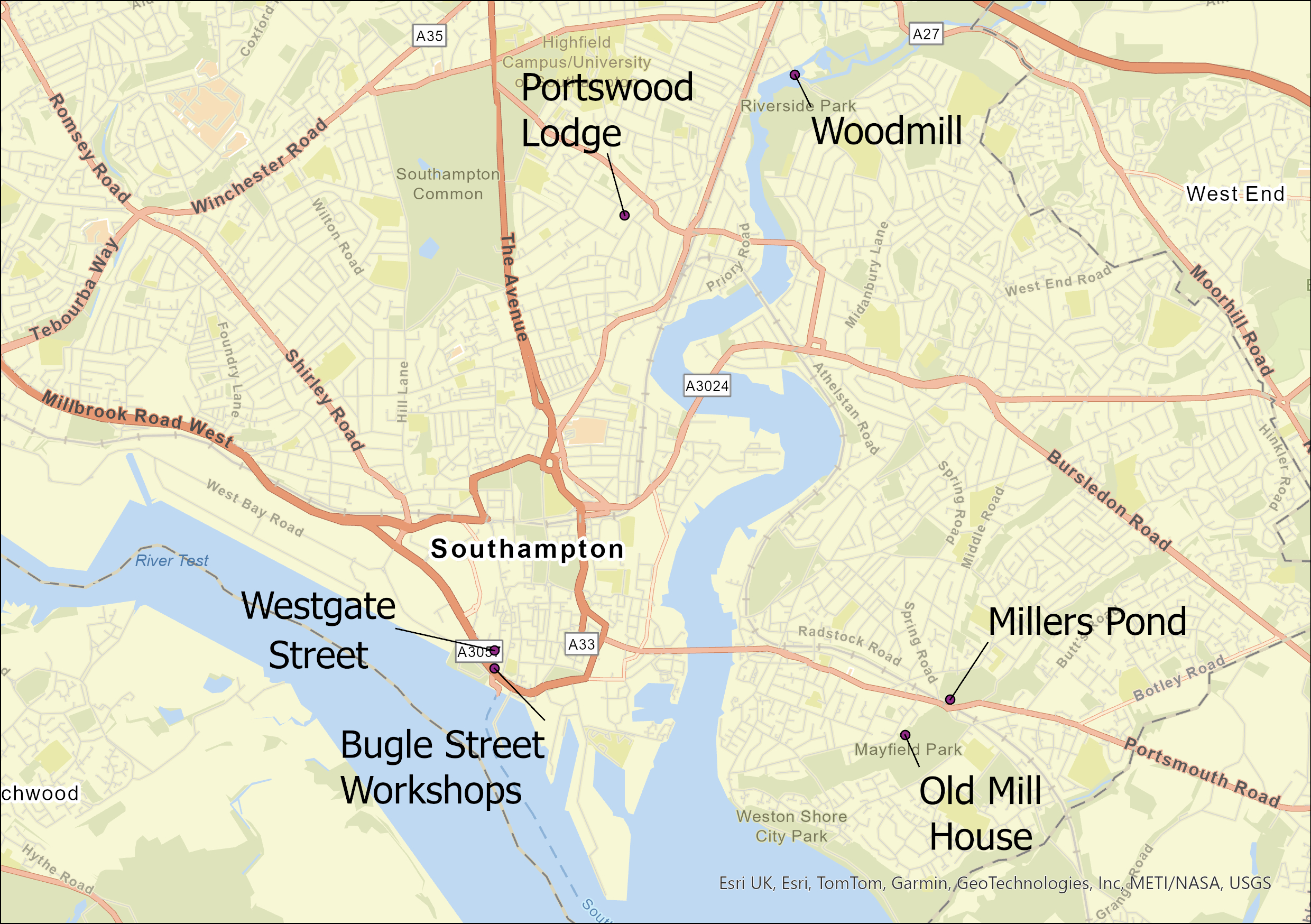

In 1770, a fire at Portsmouth Dockyard destroyed most of the Navy’s stored blocks. The Navy required Taylor to replace them as quickly as possible, using smaller blocks as used in the Bentinck trial. This necessitated larger premises, and Taylor acquired land downstream of Miller’s pond at nearby Weston, now Mayfield Park, where he built a water mill. However, water supply was inadequate for several months of the year and in 1781 he moved to Woodmill constructing alongside two existing corn mills, in timber, another mill powered by the river Itchen, with space to power some of his equipment by steam engine. (This mill burnt down in 1820 subsequently rebuilt in brick). At some point during the contract, Taylor undertook to stamp his blocks and replace any which failed. Also, his Navy contract facilitated building of Portsmouth Lodge in which he lived from about 1800.

By the late 1790’s, changes were afoot. At around the turn of the century, Walter retired, passing his firm over to his eldest son, Samuel. Marc Isambard Brunel while in New York became aware that the Royal Navy were having difficulty in obtaining their 100,000 blocks that it needed each year and designed outline plans to make the blocks, sailing to England to present his plans in 1799 to the Navy. His plans led to Samuel Bentham, Inspector General of Naval Works, recommending installation of Brunel’s machines, which could be used by unskilled workers, at Portsmouth. These machines also promised a greater output. Significantly, Brunel intended to use metal sheaves. He invited Taylor to experiment with his machines which he had patented but on 05 March 1801, Taylor declined as he used wood and considered that his father’s machines could not be bettered whereupon the Navy opted for using Brunel’s machinery at Portsmouth and when it was operational, cancelled the Taylor contract in 1803.

Walter Taylor died on 23 April 1803 and was interred at South Stoneham church on 8 May. Taylor had become a philanthropist, and many tributes were made to him; in fact, the family asked that the sermon which had recognised his contribution be reproduced in a book which required seventy-six pages. The family was large, as Walter was married three times and had fourteen children, of whom some died young.

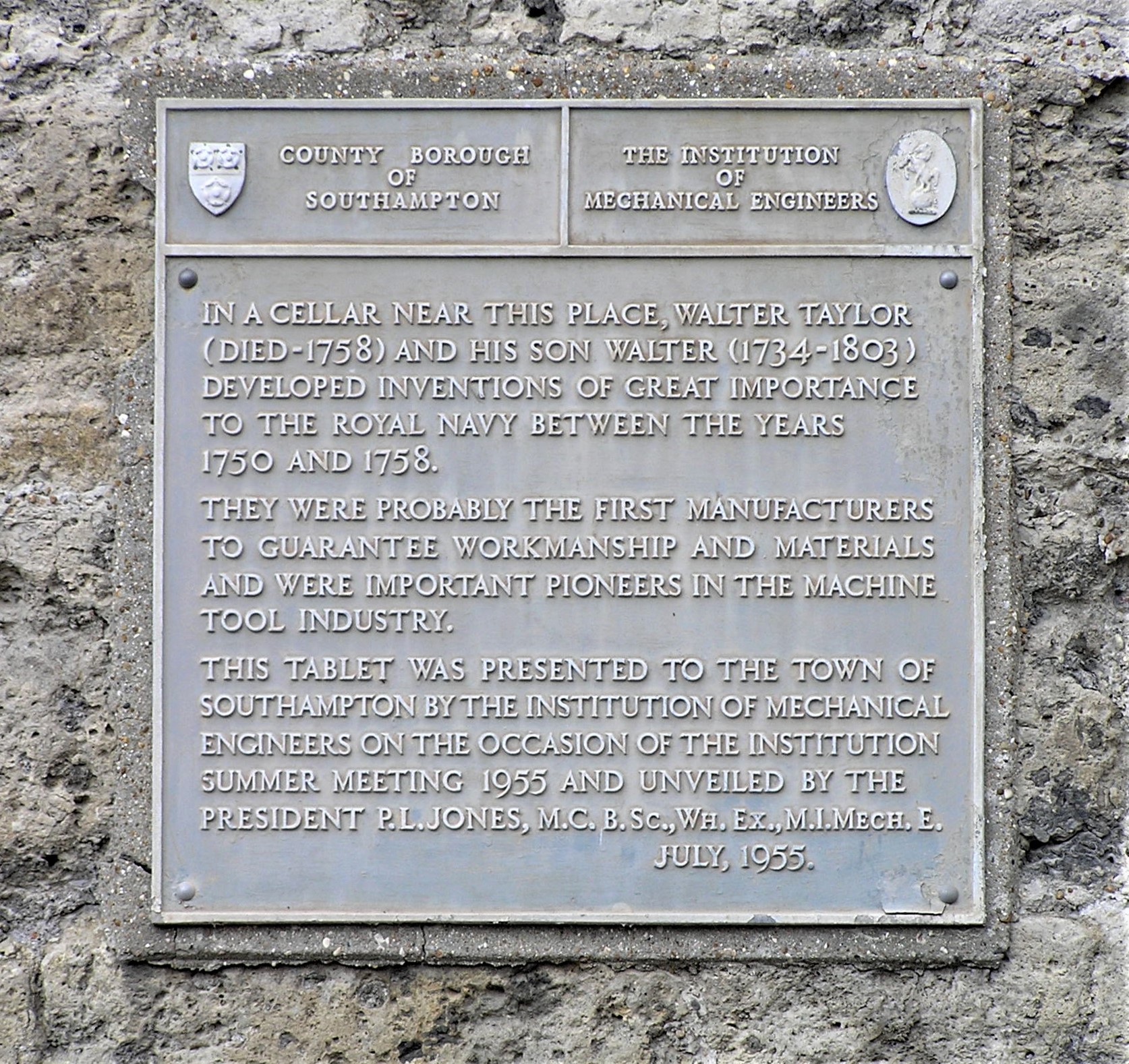

Walter’s contribution to industrial machine tool innovation was recognised by a plaque, Figure 3, presented to Southampton by the Institution of Mechanical Engineers in 1955 which can be seen at the left of the archway in Figure 3. The building to the right of the tower, now modernised, was Walter’s premises in Westgate Street.

Figure 3: Commemorative Plaque Westgate Street

Taylor’s success would not have been possible without machinery which he and his father designed, and this, with the pumps he also supplied to the Royal Navy, are highlighted in a later blog.

What a great local link. We still use the same principles in engineering to this day.