In the shadows of the Great War, the threats posed on the trading and transporting goods creep out of the vast darkness of the night to abruptly end the short life of a cargo vessel near the Isle of Wight. Joining the exclusive club of ships residing at the beds of the trading route, now known as the English Channel. Volunteer Claudio Lopez looks into the history of one unusual, yet paradoxically ubiquitous, artefact from the SS Polo.

Launched in 1913, steamship SS Polo was built in Kingston-Upon-Hull by Earle’s Shipbuilding & Engineering Co. Ltd. A three-cylinder, two-boiler and a steam engine built in house, using a screw-driven propulsion, 217 horsepower, and armed with a mounted Quick Firing Mark 1.

Although the information provided to officials by the captain stated the ship was carrying many goods, the German surprise attack was fuelled by the suspicion that the ship was smuggling mines. 12th February 1918 saw the vessel sunk by German Submarine UB57, torpedoed on her portside. Of the thirty-three crew members, three were reported missing, those who made the rescue boats taken for interrogation by the Germans. The SS Polo sunk with all its contents after eight minutes, only later found in 1975 by divers.

With the damage of time and salvage work, the Polo was only recognisable by its bell and crockery, when recovered in 1989, almost 70 years after its final descend. The challenges posed by underwater wreckage and preservation are witnessed in the conservation plan and artefact recovery for the Polo. Exposure to high pressure, erosion and corrosion result in only partial challenges presented to the recovery team. The durability of the final remaining items would determine their longevity, of which only an curious few passed the tests of time.

Figure 1: Gunsight Recovered from SS Polo, 1918 (Shipwreck Centre and Maritime Museum)

After the wreckage, a nowadays household essential of rich British history was saved from being flushed away. The Shipwreck Centre and Maritime Museum, Isle of Wight, now displays the recovered Shanks & Co. Ltd. toilet bowl “Baltic” model, finished with a Leadless glaze white clay powder to achieve the white coloured cover around the seat. A patented Victorian Pottery produced at Barrhead, East Renfrewshire, Scotland.

A simple object at first glance, yet its background offers richer historical relevance. Although Scottish production ended in 1980 after over one hundred years, by the 20th century Shanks & Co was a well-established national company and is the origins of the now know Blue Circle Industries Group, Armitage Shanks.

A now widely recognised high end bathroom manufacturer seen in many UK homes and businesses aligns the bathroom situation of the Polo crew to that of many of us now. Adding such an expense to the bathrooms by the ship manufacturer suggests a connection was in place between two well established companies in the UK. Earle’s Shipbuilding & Engineering Co. Ltd. was building ships for UK Naval merchant trade routes, establishing a renowned reputation which sold their vessels internationally, such as the Lake Titicaca SS Ollanta, used by the Peruvian nation for touring. This could example the strength of growing British naval manufacturing, with two companies thriving at a time of worldwide economic hardship.

Figure 2: Toilet bowl by Shanks & Co. Ltd, recovered from SS Polo (Shipwreck Centre and Maritime Museum)

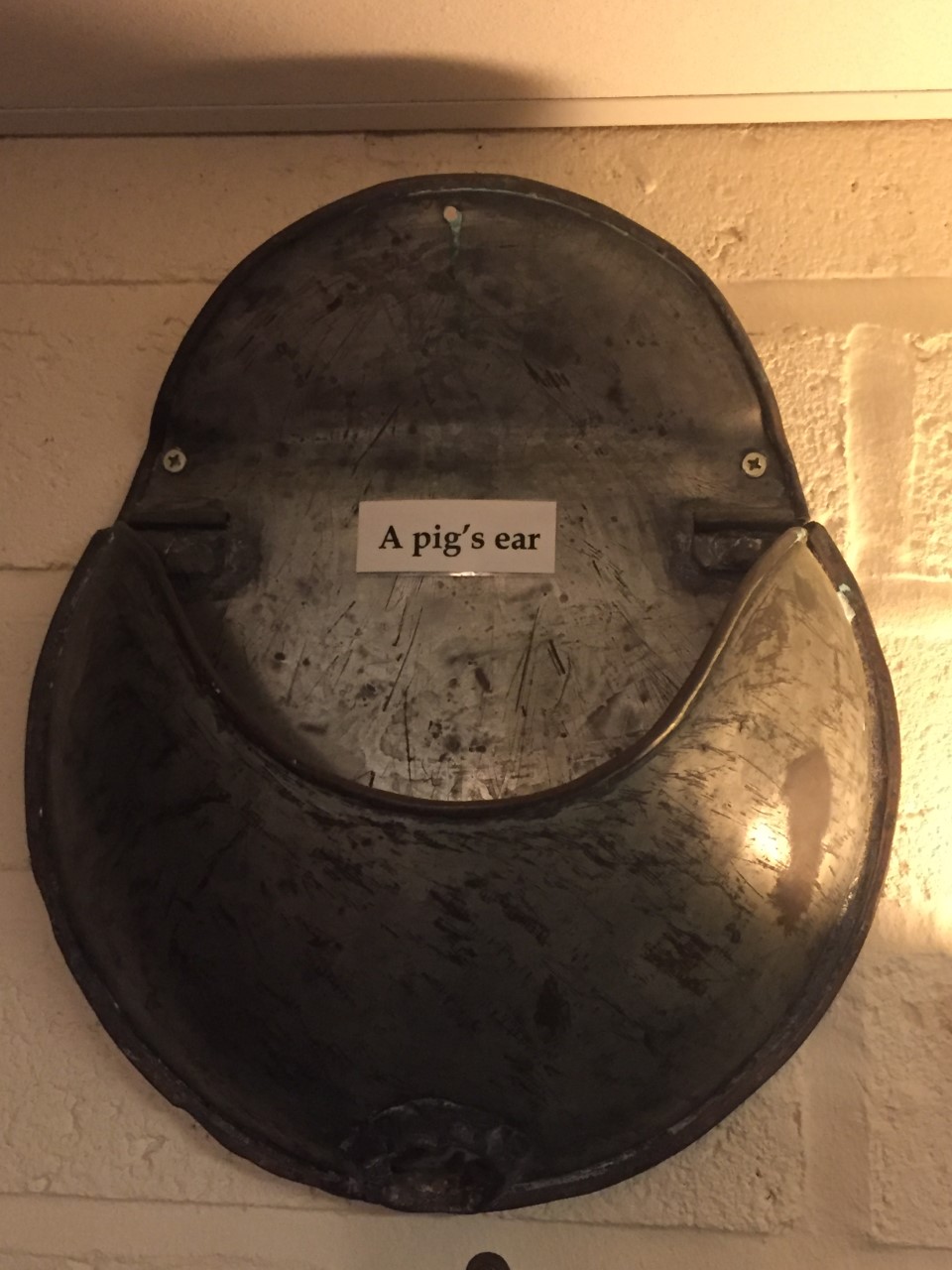

The Isle of Wight’s Museum displays a distinction between lavatory life at sea, homing also a ‘Pig Ear’s’ toilet. The Polo’s toilet contrasts the far less luxurious reality for seamen, with vessels prioritising functionality by also utilising a dry toilet. The adapted historical Pig Toilet, where the excrements would end up at sea, saved the need for plumbing to be installed during manufacturing.

Figure 3: A pig’s ear toilet or dry toilet found at the Shipwreck Centre & Maritime Museum, Isle of Wight. (Shipwreck Centre and Maritime Museum)

Though this design was an improvement to simply relieving overboard, its placement within the ship deck plan served as practical convenience for workers who were far from the lavatory room.

Both artefacts provide an insight into the working life on board, suggesting the placement of functionality over discretion, regardless of the Polo being a modern 20th century steamship. Nowadays, even though ships may still utilise dry toilets for deck workers, they would offer an amount of privacy that previous vessels did not. Despite modern improvements found now to the historical toilets, the artefacts allow us to appreciate the harsh reality of life at sea. Although the Polo did not flush its salvors with materialistic riches, its remains provide us a relevance to sailor’s life during the great war and early 20th century.