During the First World War, the need for hospital ships increased greatly to deal with large numbers of casualties. The Royal Navy operated 77 vessels during the war and transported 2,655,000 British and Commonwealth sick and wounded personnel into British Ports. Volunteer Shirley Wilson delves into the unique stories of some of heroic stories of Nurses on Ships during the First World War, examining their acts of bravery and compassion.

In 1907, the Hague Convention laid down protocols to protect hospital ships and the non-combatants they carried. The convention required the ships to not to be used for any military purposes or interfere with combat, be clearly marked with green stripes, red crosses, and white hulls and carry appropriate identification lights at night, and to help any sick and injured people, regardless of nationality. In return if they followed the rules, under no circumstances could a hospital ship be attacked or sunk.

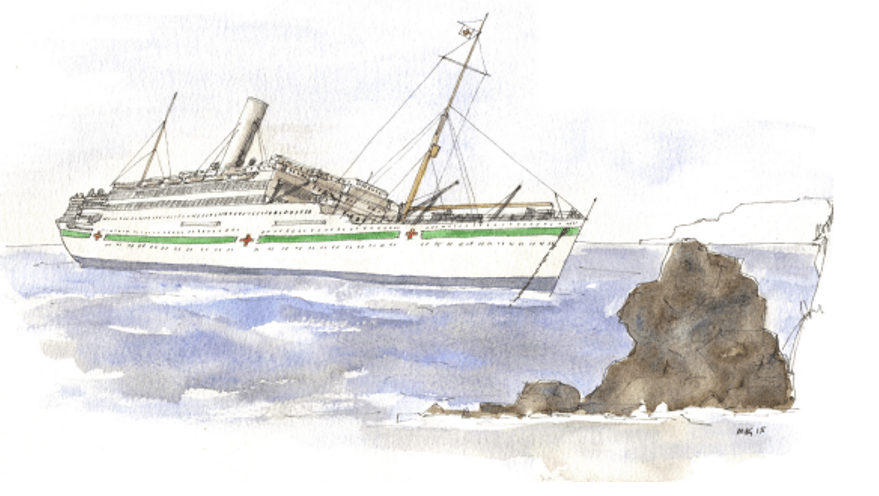

These vessels were usually converted passenger liners, some such as the Asturias and Britannic (sister ship to the Titanic) were large vessels and could carry hundreds of bed bound passengers. During the early part of the war, the Hague Convention was generally respected, but some hospital ships were lost during this time, usually because they were mined rather than deliberately targeted for attack. However, in 1917, the High Command of Imperial Germany alleged that allied hospital ships breached the Hague Convention by transporting able bodied men alongside the injured and were carrying arms so must therefore be attacked. This declaration changed the way hospital ships operated and so their traditional markings were replaced by dazzle camouflage, and some were equipped with deck guns. This was the arrangement for the remainder of the war and hospital ships sailed at night, unlit and with naval escorts. Seven British and one Australian hospital ship are commemorated at The Hollybrook Memorial in Southampton.

There are some amazing stories about how the Nurses on board ships displayed great courage and devotion during the First World War. Here are some of them.

HMHS Anglia:

This ship was sailing from Boulogne a mile from Folkestone Gate, loaded with wounded personnel from the Battle of Loos, on 17th November 1915 at around 12.30p.m, it struck a mine which had been laid by a German U boat, UC-5 and the explosion occurred well into the starboard side of the vessel, which gave no one in that area a chance of escape. However, through the organised and quick thinking of the nurses and crew, some survivors were able to get away in a life craft, but as the ship was sinking so fast there was no time to launch a second life craft. On the day it sank HMS Anglia was carrying almost 200 cot cases – service men who had lost limbs, plus 200 ‘walking wounded’. There were also a crew of 56 and a ‘compliment’ of doctors and nurses.

The sinking of the Anglia was the first occasion in the First World War where a hospital ship carrying wounded personnel was sunk by enemy action.

Figure 1: HMHT Asturias painted by Mike Greaves

‘Survivors’ stories of nurses’ heroism (from a correspondent)

These are stories told by wounded men who were on board the Anglia and mention four nurses who demonstrated stoicism and selfless humanity shown in the face of death. When the doomed vessel (Anglia) plunged it’s bows into the water at an angle which suggested instant death, the staff were faced with the problem of getting 200 cot cases up from the wards and lower wards in almost impossible conditions. Mary Rodwell was in charge of 200 cot cases, patients who were too ill to leave their beds. The water rushed into the lowest wards and the orderlies who investigated said the water was up over their heads. From the other wards, every other man who could move scrabbled as best he could up to the deck and some of the other wounded officers and men would try to save others hunting for life belts.

‘The nurses worked magnificently’, ‘but you have no idea of the difficulty of their task’. The four nurses and matron mentioned on board would not use the life belts themselves, but insisted on giving them to the men and when the destroyers came from Dover to take the wounded to safety, the nurses refused to leave the ship. They said they would stay with their men.

Private Finnar who was speaking to a representative of the Weekly Dispatch said ‘in my ward there was one Sister and two orderlies. The Sister worked like a lion. As long as I live I shall never forget her. In about seven minutes she had me extricated. When I got on deck I saw two Sisters and the Matron fastening on lifebelts and assisting the helpless men. They never gave a thought for themselves. They moved about with quick, workmanlike movement, no flustering – not for a moment did they lose their heads. They presented a sight I shall never forget – faces as white as death, hair blowing loose in the bitterly cold wind, and their hands and aprons literally covered with the blood of the men they were helping’.

‘I begged the Matron and the two Sisters to get into the boat which had come alongside. They wouldn’t hear of the suggestion. Not until the water was lapping over my feet, did I slide off, and up to then not a single Nurse had left her post in the sinking ship. It was heart rendering to see their single-minded devotion to the wounded chaps under their care. “No!” said the last Nurse I spoke to aboard the Anglia, “Our duty is to see you men off safe – we have the right to be last this time!”

You can read more about these incredible stories in this Anglia & Austrias booklet.

Nurse Mary Rodwell

Mary was born on 29th February 1880, she trained at Hendon Infirmary from 1901 – 1904, during her nursing career she worked at the Samaritan Free hospital in Marylebone and later in private nursing homes as a private nurse. When war broke out Mary Rodwell volunteered for Foreign Service, working on hospital trains from February to May 1915, after which she joined HMS Anglia.

The nurse ‘with them to the last’ is suffragette, Mary Rodwell. She was the only nurse to go down with the ship, refusing to leave the helpless men, choosing instead to comfort them in their final moments. The last time she was seen on deck by the Matron shortly before the explosion she was fetching warm woollies for the casualties below, a selfless and futile gesture that she must have known would lead to her death. There was no way off the boat for her patients and she was unwilling to let them die alone. She was also a woman who was fighting for the right to vote, which is quite astonishing.

The British Journal of Nursing stated: “Her last minutes were spent in caring for them as when the explosion came she was ministering to the wounded”. The Nursing Times reported that Mary Rodwell was injured and drowned. Mary Rodwell’s body was never recovered. The Matron, Mrs Mitchell who was rescued from the Anglia and the other two Nurses, Meldrum and Malton would later receive the Royal Red Cross.

Alice Meldrum

Alice Meldrum, QAIMNS (Queens Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service), Reserve, was twenty five years old at the time of sinking on the Anglia, wrote an account of the situation, here is a short excerpt: ‘there was no panic whatsoever and when one realises that the majority of cases they were suffering from fractured limbs, severe wounds and amputations, it speaks volumes for their spirit, their grit and real bravery, for they must have suffered agonies of pain’.

As mentioned earlier, she was awarded the Royal Red Cross 2nd class for her services and devotion to duty (the war on hospital ships) during the sinking. She also wrote and published a small booklet of her experience of life on a Hospital Ship.

HMHS Glenart Castle

With the passing of time our links to the past will inevitably disappear as there are no longer any soldiers or nurses alive who served in the First World War, this is why memorials are so important as part of our link to the past and to recognise the service that these personnel served. Women served at sea aboard hospital ships, passenger and cargo vessels and ferries as nurses, medical staff, stewards and cooks. Thirteen women of the nursing services are commemorated at Hollybrook. All eight nurses aboard the hospital ship Glenart Castle were lost when it was torpedoed off Lundy in 1918. There was a total loss of life of 162 This ship was originally named the Galician, an ocean liner of the Union-Castle line and in 1914 Glenart Castle was requisitioned for war service as a hospital ship and given the new name. On the night of 26th February 1918, the Glenart Castle left Newport, South Wales sailing for Brest in France to collect the wounded. On board were a crew of 122 and 64 Royal Army Medical Corps, nurses and chaplains. Fishermen in the Bristol Channel reported seeing the ship clearly lit up with green hospital lights and red markings, despite this the Commander of German U Boat UC-56 ordered the attack.

The ship sank in eight minutes with the loss of 162 lives. 57 are commemorated at Hollybrook (47 Royal Army Medical Corps, 8 nurses and 2 Royal Army Chaplains). Only 32 people survived. Here are the stories of those nurses.

Figure 2: A 3D Model of the Hollybrook memorial which you can find on Sketchfab here

Matron Kay Beaufoy

Kay was born on 20th December 1868, at Birmingham and undertook her probationary training at the Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital, from October 1893 to January 1898. She spent time as a Sister in the operating theatre and also a Sister on the male medical wards. She had a varied nursing career before re-joining the QAIMNS on 17th August 1914, where she served on the HMHS Dover Castle in 1916, and then joined as Matron on the HMHS Glenart Castle in November 1917. The National Archives show that Matron Kay Beaufoy’ records show she had travelled over 60,000 miles since the beginning of the war and had more than 30,000 patients under her care in that time. More information can be found in the National Archives document here.

Staff Nurse Rebecca Rose Beresford

Rebecca was born on 18th June 1878 in Sydenham. She undertook her probationary training at the Taunton and Somerset hospital during 1907 to 1912, by which time she was covering Sister’s duties. She also worked as a surgical ward sister in temporary hospitals in Bavois, Switzerland and Marne, France. She joined the staff of the War Hospital for Prisoners in Belmont, Surrey in May 2017 on the same day as Staff Nurse Edith Blake and they became good friends. Edith then moved to work on this ship, so Rebecca requested a transfer to the Glenart Castle and she started on 19th February 1917.

Staff Nurse Edith Blake

Edith was born in Sydney and prior to the First World War she had worked at a Coastal hospital in Sydney. She was transferred to the QAIMNS following a special request in April 1917 as she had spent time on the HMHS Essequibo and 18 months in general hospitals in Egypt, including the War Hospital for Prisoners in Belmont. Edith joined HMHS Glenart Castle on 17th November 1917 and at a memorial service for Rose Beresford and Edith Blake in March 1918, they received high tribute for their work.

Staff Nurse Elizabeth Edgar

Elizabeth was born in Glasgow in 1880, but spent her childhood in Durban, South Africa as her father was an engineer in Natal. She undertook her basic nursing training in Natal from 1898 to 1903, and eventually became a Charge Nurse in the operating room at Greys’ hospital in Natal. After a varied career in South Africa and then in Clydebank, Scotland. She enrolled with the QAIMNS in July 1916 and joined the Glenart Castle a short while after.

Staff Nurse Charlotte Edith Henry

Charlotte was born in Essex in 1877, she trained in Plymouth at the South Devon and East Cornwall hospital from 1897, and she progressed to being a temporary Sister and then undertook private nursing from 1905 to 1908. Following some other nursing posts in Droitwich and Redditch in the Midlands and Serbia at a typhus hospital, she enrolled with the QAIMNS in 1916. In 1917, Charlotte alongside her four sisters, who were not married, changed their name by deed poll from Heinrich to Henry. Charlotte’s sister, Gertrude, also a nurse had been subject to a lot of anti-German sentiment during her nursing career which prompted them to change their name.

Staff Nurse Mary Mackinnon

Mary was born in Arisaig, Inverness shire and was called up for duty at the second Southern General Hospital in Bristol in October 1916. She renewed her contract with the TFNS in January 1918 and was then transferred to the Glenart Castle on 15th February 1918 destined for Salonika.

Sister Jane Evans

Jane was born in Brighton in 1881 and worked at the Victoria Park Chest Hospital, Bethnal Green from 1908 to 1910, she then undertook her training at Leicester Royal Infirmary from 1910 to 1913. She became a staff nurse and worked in a nursing home, then private nursing and at the Brighton isolation hospital. Jane joined the QAIMNSR in March 1915.

Sister Rose Elizabeth Kendall

Rose was born in Birmingham in 1887, she completed her probationary training at the Infirmary in Erdington in 1908, was promoted to Staff Nurse and then Ward Sister by 1912. She signed up to the QAIMNS in October 1914 and renewed this in 1915 and 1917. She joined the Glenart Castle in November 1917.

These stories represent a snapshot of these women’s lives, having a varied nursing career before joining the Glenart Castle and from the dates these women joined the ship, their lives were cut short. It also demonstrates the range of skills, talent and experience that they brought from across the world to nursing sick and wounded men during the First World War.